The following article by Charles Hartley originally appeared in The Courier-Journal on 7 Sep 2014. It is archived here with additional information for your reading enjoyment.

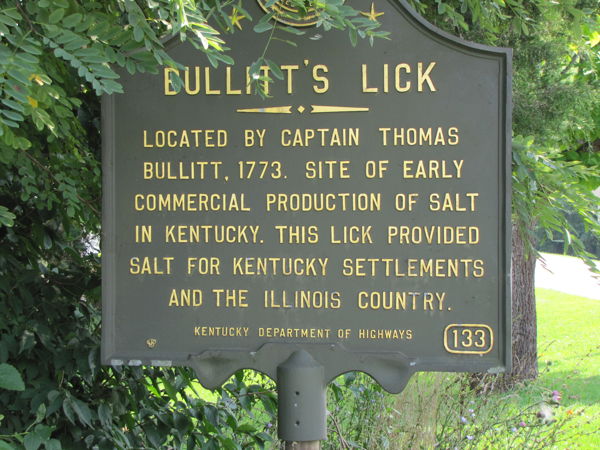

Native Americans had known about salt licks in Kentucky for centuries, and French explorers were in the region as early as 1739. So by 1773, when Captain Thomas Bullitt visited what would become known as Bullitt's Lick, the licks' locations were common knowledge.

Salt is an essential element in the diet of humans and animals. It is one of the most effective and most widely used of all food preservatives. These two facts help to explain why the salt found in this region was so important to those who first arrived in Kentucky. Salt licks attracted wildlife like bison, deer, turkeys, and all sorts of creatures because they provided minerals that were needed in their diets. It is no coincidence that some of the early travel routes wound and meandered to include locations of salt licks. Long before settlers entered Kentucky, wild animals discovered various salt springs and used them as natural salt licks.

In 1774 John Floyd led a group of surveyors into Kentucky with the task of surveying tracts of land for men back in Virginia who had received land grants for military service in the French and Indian War. Thomas Hanson kept a journal of the trip.

According to Hanson's Journal (12 May 1774), James Douglass, or another member of the Floyd party, surveyed 1000 acres for William Christian that included the Big Bone Lick, located in what is now Boone County. Another entry (13 Jun 1774) indicates that Douglass surveyed another 1000 acres for Christian that included Bullitt's Lick.

Thus, Colonel William Christian laid claim to the two most significant salt licks in Kentucky. I speculate that he had been specific in his instructions to include the licks in his claimed land, knowing their value.

In 1909, Virgil Anson Lewis described Christian's career this way. "He was a member of the House of Burgesses from Fincastle county in 1774, and was Colonel of his county at the time of Dunmore's war. In 1775 he was a member of the Virginia Convention that assembled March 20th, and same year he became Lieutenant-Colonel of the First Virginia Regiment of which Patrick Henry was Colonel. In 1776, he became Colonel of the first battalion of Virginia and commander of an expedition against the Cherokee Indians. In 1780, he commanded another expedition against that nation; and was the next year, appointed by General Green, head of a Commission to conclude a treaty with them."

He was well connected, having married Patrick Henry's sister. Having distinguished himself as a military officer, for his service he was awarded numerous Kentucky land grants, which would soon include the salt licks.

However, Christian himself played no part in the day-to-day operations of the saltworks that developed at either location. In fact he sold the Big Bone Lick site to David Ross in 1780 for 1350 pounds, much more than nearby tracts were bringing. While he did move to the Louisville area in 1785 from Virginia, he left the operation of Bullitt's Lick in the hands of an agent.

Moses Moore leased the entire lick from Christian's agent, and sublet it to a number of independent furnace operators.

When Christian was killed in 1786, while pursuing an Indian party, his will left "Saltsburg," as he called the works at Bullitt's Lick, to his infant son, with the boy's mother as guardian. When she too died, Patrick Henry, the boy's uncle, was made his guardian. But nothing really changed at Bullitt's Lick. Moses Moore traveled to Virginia and secured a new lease directly from Patrick Henry.

Robert McDowell identified the names of a number of the men who, at one time or another, leased furnace locations from Moses Moore. They included Archer Dickinson, T. W. Cochran, Witle Barrow, Daniel Banta, William Hines, Nathaniel Harris, Isaac Skinner, John McDowell, James Latham, Andrew Price, Jesse Hood, Benjamin Stebbins, Samuel Hancock and John Moore.

And then there was Jonathan Irons who, according to McDowell, "could handle his rowdy crew of saltmakers except when he was drunk - which unfortunately appeared to be most of the time."

He purchased land on the buffalo track that ran from Bullitt's Lick to another salt lick that was located along Long Lick Creek, right about where Highway 61 crosses the creek today. His land lay on both sides of Salt River where the track crossed it, and he began prospecting for salt water. Luck was with him, and he found it almost in the river's bed, just steps from the buffalo track. Thus Iron's Lick joined the growing list of saltworks in this area.

Henry Crist bought part of Bullitt's Lick in 1814, and eventually acquired the whole lick; but by that time salt making was barely profitable with the discovery of cheaper sources elsewhere.

The saltworks operated until about 1830 when the fires were allowed to go out under the last kettle, and an era came to an end. Today, Bullitt's Lick is quiet; gone are the wells, the fires, the bubbling kettles, the sweat-streaked men; nothing remains but a historical marker to show that it ever existed at all.

Copyright 2014 by Charles Hartley, Shepherdsville KY. All rights are reserved. No part of the content of this page may be included in any format in any place without the written permission of the copyright holder.

The Bullitt County History Museum, a service of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is located in the county courthouse at 300 South Buckman Street (Highway 61) in Shepherdsville, Kentucky. The museum, along with its research room, is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Saturday appointments are available by calling 502-921-0161 during our regular weekday hours. Admission is free. The museum, as part of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization and is classified as a 509(a)2 public charity. Contributions and bequests are deductible under section 2055, 2106, or 2522 of the Internal Revenue Code. Page last modified: 12 Sep 2024 . Page URL: bullittcountyhistory.org/memories/licks.html