On a rainy Monday afternoon at the Tenth Street railroad station in Louisville, Henrietta D. Huber signed a deed that read, in part, "This deed, between Mrs. Henrietta D. Huber (widow) of Bullitt County, State of Kentucky, party of the first part, and Mrs. Clara M. Barbour wife of John R. Barbour of the same county and state of the second part.

"Witnesseth: that in consideration of six hundred and thirty five dollars, three hundred and twenty five dollars of which is cash in hand paid, the receipt whereof is hereby acknowledged and two lien notes of one hundred and fifty-five dollars each, payable in one and two years after date respectively with six percent interest and for the payment of which a lien is hereby expressly retained upon the property herein conveyed … the party of the first part does hereby grant and convey to the party of the second part in fee simple … 10¼ acres, lying in Bullitt County, Kentucky near Huber's Station, and being part of the property obtained by first party under the will of her husband J. H. Huber. The said party of the first part also hereby grants and conveys to said second party a passage-way, fifteen feet in width from the land herein conveyed, beginning at the northwest corner of the land herein conveyed and extending west to a point on the east line of the railroad track, thence parallel with said railroad track south to Huber's Station, all of said passageway to be fifteen feet in width."

Her signature on the deed was witnessed by William F. Ingram, a Jefferson County Notary Public, who was also then the treasurer of the Louisville Water Company.

Mrs. Huber was at the Tenth Street station that evening preparing to take a trip to visit relatives in Texas, and John Barbour had arranged for Mr. Ingram to meet her there to witness her signature on the deed.

In a later deposition, Mr. Ingram stated, "Mrs. Huber was there with one of her daughters, and she presented me with a deed; I had my notary seal along. I took her acknowledgment and asked her daughter as near as I can recollect to step to one side while Mrs. Huber signed. She signed the deed and then she presented two notes and endorsed those two notes. Before that she handed me the deed and asked me to give it to Mr. Barbour. When she handed me the two notes I thought she had made a mistake as in any deed generally given is a cash payment, and consideration of two notes; and I didn't understand why she should give me the two notes at that time. I said 'Mrs. Huber, what shall I do with them?' She said 'Give them to Mr. Barbour.' I said 'Both the notes?' She said 'Yes.'"

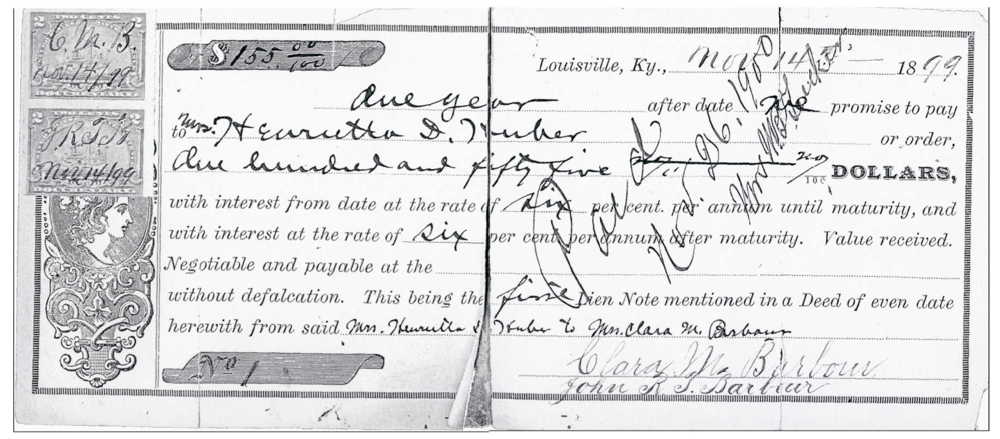

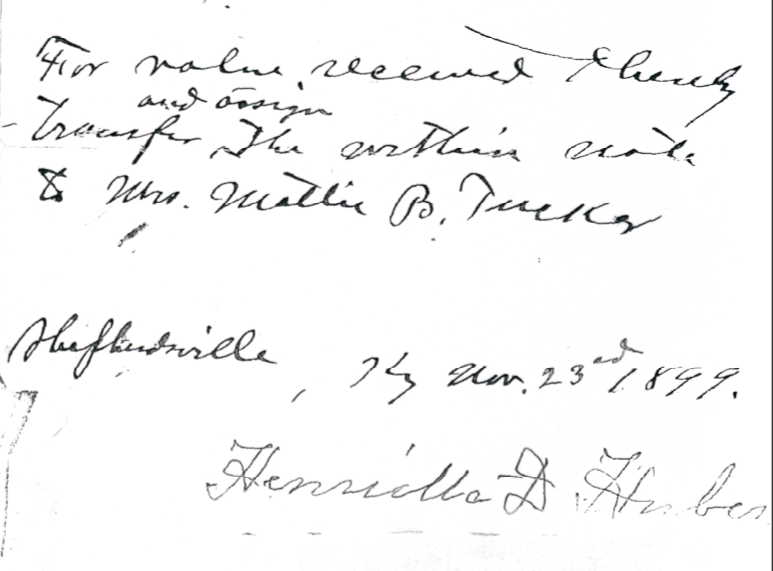

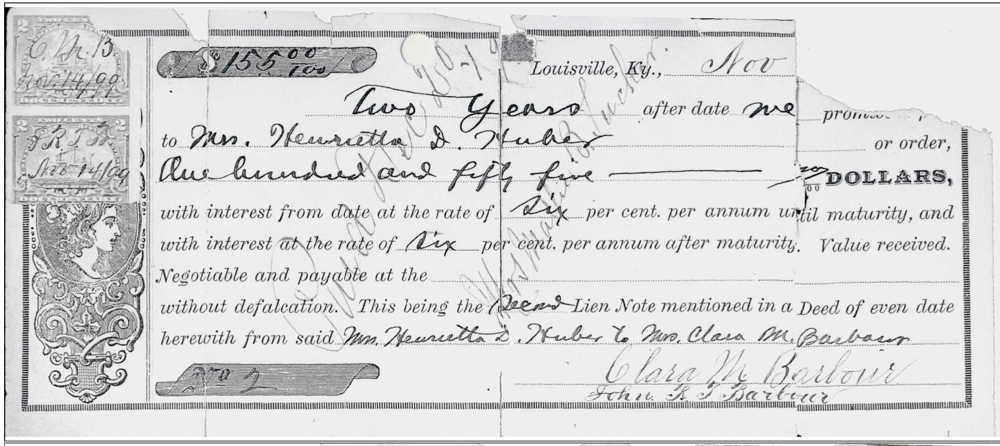

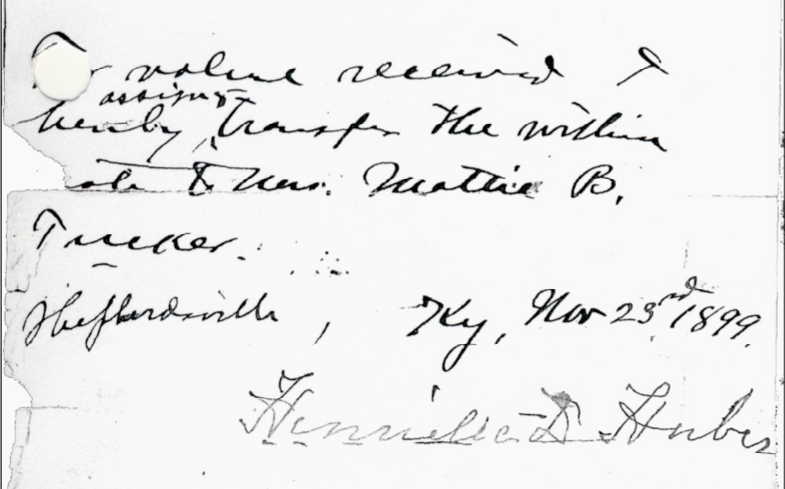

By signing the deed, Mrs. Huber acknowledged the receipt of the initial $325 payment. An examination of the lien notes shows that Mrs. Huber endorsed each one by signing her name on the back beneath the statement: "For value received I hereby assign and transfer the within note to Mrs. Mattie B. Tucker."

As Mr. Ingram indicated, she gave him no reason for either endorsing the lien notes, or for why he was to give them to John Barbour.

The first lien was initially made payable to Mrs. Henrietta D. Huber, dated November 14, 1899, for $155.00 with interest at six percent per annum. This note was due in one year. On the back we see Mrs. Huber's signature, dated November 23, 1899 at Shepherdsville, although we know she signed it three days earlier in Louisville.

Note also that Mrs. Tucker wrote "Paid Nov. 26, 1900" across the front of the note and signed it.

As we will show later, an attorney named Harry F. Means represented Mrs. Mattie B. Tucker in her financial affairs. At the request of Mr. Barbour, Mr. Means prepared the written deed, and the two lien notes ahead of time, and wrote the statement on the back which Mrs. Huber endorsed. At the time he prepared it, it was apparently assumed that Henrietta Huber would sign it in Shepherdsville on the 23rd.

The second lien note is almost identical, except for when it was due (two years) and when it was paid. Mrs. Tucker wrote across the front that it was paid on December 20. The year it was paid is missing due to a tear in the document, but other evidence shows that it was paid in 1901.

At this time the relationship between the Barbours and Hubers was very friendly. Indeed, Henrietta and her daughter Mary depended on John Barbour for many things.

In a later deposition, Mary Huber, who by that time was married to Francis Hagan, made the statement that "Mr. Barbour attended to all of my business, and my mother's also, every bit of it. We never did anything without first consulting him. … He always managed everything for us, even the slightest details."

Barbour concurred in another deposition statement when he said, "We were friends, you know, and I was helping them along all I could. We were the best of friends at that time."

Yet by the time the second lien note was paid off, things were very unfriendly, as we will see.

When John Barbour gave a check for payment of the second lien note to Harry Means, Mrs. Tucker's attorney, it was contingent on Mr. Means obtaining the release of the lien on the property deed.

Mr. Means later stated, "At the time I first went to Shepherdsville to have the lien released, I saw Mr. Hagan and asked him, as executor or administrator of the Huber estate to release the lien. I had the check for the last note, and the first note which had been paid at that time. That was before the last note had been paid, and I had the first note canceled, and in my possession, which I took to show Mr. Hagan down at Shepherdsville in order to get him as executor of the estate to release the lien that was retained in the deed of conveyance."

When asked what Mr. Hagan's response was, he said, "He refused to release it."

John Barbour removed the stipulation and allowed the check to be cashed to pay off the lien note. Then he hired Charles Carroll, a local attorney, to represent his wife in a civil suit to obtain the release of the liens on the deed.

This case would eventually go to the Kentucky Court of Appeals, thus preserving the depositions taken by both sides, and allowing us to gain a better understanding of this conflict that led to Hagan's death.

While depositions taken under oath require the deposed to tell the truth, as he or she knows it, the depositions taken in this case may lead us to the conclusion that someone was deliberately lying. The more difficult challenge will be to decide who was telling the truth.

We will next examine the civil suit as it progressed through the court system, including the testimony given in depositions and the court rulings. Along the way we will also see how tensions rose to the point where each side was accusing the other of violent acts.

Copyright 2024 by Charles Hartley, Shepherdsville KY. All rights are reserved. No part of the content of this page may be included in any format in any place without the written permission of the copyright holder.

The Bullitt County History Museum, a service of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is located in the county courthouse at 300 South Buckman Street (Highway 61) in Shepherdsville, Kentucky. The museum, along with its research room, is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Saturday appointments are available by calling 502-921-0161 during our regular weekday hours. Admission is free. The museum, as part of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization and is classified as a 509(a)2 public charity. Contributions and bequests are deductible under section 2055, 2106, or 2522 of the Internal Revenue Code. Page last modified: 13 Aug 2024 . Page URL: bullittcountyhistory.org/bchistory/murder/murder-3.html