The following contains excerpts from a research book on the train wreck in Shepherdsville on December 20, 1917. Written by Charles Hartley, the book is available at the Bullitt County History Museum in Shepherdsville. More information about this book is available on another page.

On December 20, 1917 the local "Accommodation" train pulled into Shepherdsville just after sunset. While local patrons disembarked and additional passengers boarded the local train, the Cincinnati to New Orleans "Flyer" express train bore down on Shepherdsville. Moments later a collision left death and destruction in its wake. This is the story of that terrible time.

With Christmas approaching, residents from outlying towns made their way to Louisville, seeking presents for loved ones. Others found themselves in the big city on business errands, or to visit a doctor or a hospitalized love one. Each would be returning home by train this evening.

The train that carried them home was known as the "Accommodation," a name that mocked how many regarded it. The passenger cars used for the "Accommodation" were largely constructed of wood, were drafty in the winter months, often dingy or outright dirty, and subject to overcrowding at times.

The "Accommodation" made its way from stop to stop, frequently picking up and dropping off passengers. In Bullitt County alone it regularly stopped at Brooks, at a small station at Gap in the Knobs, then at Shepherdsville and almost immediately across Salt River for patrons who lived south of that river. Below Shepherdsville it traveled to Bardstown Junction where it left the main line and headed east to Chapeze and then on to Deatsville, Samuels and points beyond including Bardstown and Springfield. It was also known to make additional stops along the way for the convenience of passengers who lived in remote areas.

On this evening the "Accommodation" train, designated as No. 41, would pull a baggage car, followed by a combination smoker and colored car, and finally the first class day coach. It would be crowded with perhaps a hundred passengers.

The "Accommodation" train was due to leave the Tenth Street station at 4:30 (Central Time), but was delayed and left at 4:36 p.m. It is not known how many stops it made along the way, but according to W. E. Sanders, the telegraph operator at Brooks Station which is 13.9 miles from Louisville, it arrived there at 5:12, unloaded a few passengers, and left a minute or so later. At that time it was still running about six minutes late.

Meanwhile, back at the Tenth Street station, the train known as the "Flyer" with nine cars of mostly steel construction left the station at 4:53, twenty-three minutes late. This train was designated as No. 7. It would normally travel south to Nashville, on to Birmingham, and end its run in New Orleans. The engineer, William Wolfenberger, was expected to make up lost time along the way.

When No. 7 passed the F. X. tower (one of the switching towers at track junctions), which is 3.7 miles from the Tenth Street station, J. W. Sams, train dispatcher at Louisville, called W. E. Sanders at Brooks Station and advised him to inform the conductor of No. 41 of this, and to suggest to him that he "head in" at Shepherdsville if he didn't think he could reach Bardstown Junction before No. 7 overtook him.

When No. 41 reached Brooks Station at 5:12, Sanders informed Conductor Campbell of No. 7's progress and the message that he should "head in" at Shepherdsville unless he thought he could make it to the spur line at Bardstown Junction before No. 7 overtook him. Since these were verbal orders it was not required that Sanders also tell the train engineer.

As No. 41 pulled away from Brooks Station, Campbell told the train porter, Ernest Chase that No. 7 was following them, and he had been told to "head in" at Shepherdsville unless he could make it to Bardstown Junction. Chase would later report that they made three more brief stops on the way to Shepherdsville, a distance of five miles.

As they approached Shepherdsville, Campbell made the decision to make their regular stop at Shepherdsville, and to determine there where No. 7 was, and whether to "back in" to the siding at Shepherdsville or not.

No. 7 passed Brooks Station at 5:24. It did not stop, but blew the right of way, four short blasts. The right of way was given him by the usual signal of changing a red to a green light, and he blew two short blasts in acknowledgment and went on his way.

At about that same time, No. 41 came to a halt on the main line at Shepherdsville rather than "heading in" at the siding. The train unloaded fifteen to twenty passengers. When station operator, Jesse Weatherford, had no information for him about No. 7, Conductor Campbell hurried to the depot to check on No. 7's progress. Weatherford later said that he put up the board, indicating that No. 41 was on the track, and helped with the unloading of the baggage.

Meanwhile Chase, the porter, met Campbell coming from the office of the operator, and the conductor told him to tell the engineer to "back in" at the switch. This meant that the train would have to pull forward perhaps two hundred feet or more so that the rear car was past the junction of the siding before it could begin to take the siding and clear the main track. Chase went up to the engine, told the engineer, and rode on the front end of the engine down the track until they reached the switch.

At 5:27 No. 7 passed Gap in the Knobs. Wolfenberger would report later, "I sounded the station signal, one blast from my whistle, when we were about a half mile from Shepherdsville. Then I blew four blasts for orders. I could see the signal only dimly, and it was green, our signal to proceed if we had seen it change from red to green. I did not see it change, as it appeared green when I first saw it."

Continuing, he said, "Oftentimes an operator gives us the signal before we call for it, and I believed it had already changed from red to green, meaning for me to proceed."

When No. 41 reached the switch, Chase dropped off the train and threw the switch so that the train could begin to back in to the siding. Throwing the switch changed the flag from green to red. At this time the flagman for No. 41, Lawrence Greenwell, should have been well behind it to drop torpedoes and fusees as warning signals to No. 7. No one would later report seeing him there.

Wolfenberger later reported, "I saw the signal change to red and I applied the emergency brakes. Had the signal been given by Weatherford when I blew for the board, I believe I could have come to a stop."

Weatherford saw the headlight of No. 7, seized a red lantern and frantically tried to flag it down, but it was too late. He watched in horror as it passed by him, unable to stop in time.

After Chase threw the switch he looked up suddenly and saw No. 7 bearing down upon him. He "leaped to the side and jumped the fence."

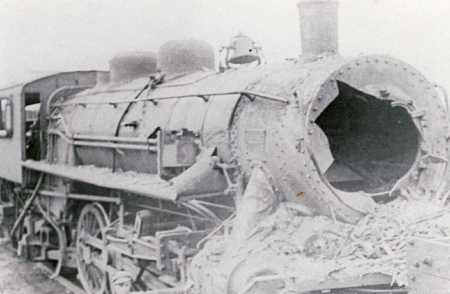

It is impossible to know with certainty exactly what happened, but it seems that the "Flyer" struck the rear of the passenger car at a speed of perhaps twenty-five miles per hour; its speed having been reduced by braking action.

Its forward momentum and great weight imploded the back of the car sending fragments of wood and glass forward into the car and its passengers. As it continued forward the sides of the car began to buckle and shatter, causing the roof to drop down on the passenger's heads.

Benches and their occupants were thrust forward, or ground under by the forward progress of the engine. Some of the passengers nearest the point of impact were killed instantly, never knowing what hit them. Others were battered about, suffering life-threatening injuries.

The engine continued forward the length of the car, shattering it completely, and scattering splinters and broken glass debris and bodies to both sides of the track. Other bodies were trapped on the massive engine when it next smashed into the smoker car.

No. 7's momentum stalled about half way through the smoker car, but the whole car was damaged as it was pushed forward into the baggage car which was also damaged as it was caught in a vise between the smoker and the engine. Parts of both cars fell down the side of the track into a small underpass at what is now Second Street near the Ridgeway Library. Later, bodies would be found in this wreckage.

Feeble cries for help and others of anguish came from the wreckage, and those who had witnessed the crash moved quickly to help. The town's three doctors were on the scene in a few minutes and every house and store was thrown open to care for the dead and dying. Poor light hampered rescue along the track, making it difficult to locate silent victims.

Christmas dolls, only recently clutched in the hands of children, were scattered about the track; their limbs askew in unnatural postures, much like the young battered bodies of their owners. A supply of Christmas candles found on the ruptured baggage car served to provide a bit of light for rescuers in the gloom.

The L & N office in Louisville was notified of the tragedy. Immediately steps were taken to organize a relief train. Calls were broadcast for physicians and nurses, and by 6:30 the train left for Shepherdsville with eleven Louisville doctors and several surgeons and within half an hour pulled up at the station at Shepherdsville.

The Louisville Evening Post of December 21, 1917 reported, "When the relief train reached Shepherdsville the physicians found that much of the preliminary work had been done by the local physicians and by the people of that city, and the doctors and nurses on the relief train applied themselves to completing the preliminary work and to preparing the injured to be removed to the hospital in Louisville."

The first relief train arrived back in Louisville at 11 p.m. It backed into the siding near Sts. Mary and Elizabeth's Hospital and ten policemen were required to hold back the frantic kinspeople who had rushed there, seeking word on their loved ones. The injured were carried on stretchers by soldiers from nearby Camp Taylor from the train to the waiting hospital.

"Thirty-nine injured persons were admitted to the hospital, while many persons who were in the wreck and who were brought there on the relief train, called for taxicabs and were taken to hotels."

About midnight a second train was dispatched to bring the dead to Louisville. It returned at 3:45 a.m. with the bodies which were taken by army ambulances to the undertaking establishment of Lee E. Cralle at Sixth and Chestnut streets.

Blame for the accident was swift and widespread, but tt would be two months before the Interstate Commerce Commission in Washington issued its ruling on the cause of the wreck. Responsibility was assigned to negligence of the conductor and fireman of No. 41 and the failure of the engineer of No. 7 that crashed into it to observe a signal. No other blame was assigned.

The Louisville and Nashville railroad paid out thousands of dollars in compensation to those injured, and to the families of those killed in the 1917 wreck.

The following lists contain the names of those killed, and those injured in the train wreck according to the various sources available to me. This includes the various newspaper lists, not all of which agreed on who was killed and injured; as well as obituaries and other printed sources. In those cases where the person was misidentified, or not fully identified, I have provided the corrected names found in other sources such as census and death records.

Death certificates have not been found for all of those listed as killed. Indeed, a few of those listed, have not be identified in any other way except in the newspaper lists of the time. Certainly there may have been additional people injured that do not appear here.

Those Killed (approximate ages given):

Father Eugenio Angelo Luigi Bertello (32), Joshua Bethel Bowles (50), Hollie Bridges (17), Josie Bridges (18), Mahlon Campbell (48), Carrie Barkhurst Cherry (39), Redford Columbus Cherry (46), William Redford Cherry (5), Raymond Thomas Craven (3), George C. Duke (34), Virginia Frances Duke (6), Lawrence C. Greenwell (37), Henry Zollicofer Hardaway (55), Martha E. "Mattie" Harmon (69), Joseph Raoul Hurst (8 mos), Louisa Losson Hurst (20), Catherine "Kate" Ice (35), Charles William Johnson (66), Silas C. "Sie" Lawrence (68), David Henry Maraman (37), Emily Haycraft Mashburn (40), Elizabeth McElroy (17), Amelia Sue Miller (33), Lillian Jones Miller (31), Mabel Brown Miller (36), Walter McMakin "Mack" Miller (36), Garnette McKay Moore (47), Lucas Moore (56), James Hartwell "Jimmy" Morrison (15), Cora May Shadburne Muir (49), George Shadburne Muir (16), Nathaniel Wickliffe Muir (65), Frank Linnis Nunn (28), Estella Harris Nutt (33), Forest Overall (16), Maggie Mae Overall (24), Elizabeth "Bettie" Phillips (58), David Phillips (51), John T. Phillips (55), Alice May Pulliam (34), Emory Beamis Samuels (42), Thomas William Schaefer (17), Carrie May Simmons (39), Mary Alethaire Simms (19), William Thomas Simms Spalding (24), James W. Stansbury (46), Ben Talbott (59), James W. Thompson (48), N. H. Thompson (?)

Images of the death certificates for most of these may be viewed by following this link.

Those Injured:

Henry Bowman 63), James Madden Bradbury 39), Margaret Belle Bradbury 38), Charles Arthur Cahoe 37), James Marion Carrico (34), Walter Augustine Carter (18), Benjamin Chapeze (54), Ed Clarkson (?), Eliza Marie Craven (24), Annie Craven (10 mos), Frank E. Daugherty (46), John Gilmore Dodds (49), Ottie Satterfield Duke (31), John Ford (48), Jefferson Davis Gregory (56), Nathaniel Wicklyffe Halstead (64), Natalie Halstead (18), Edith Hatfield (19), Lena Hatfield (46), Thomas W. Hoagland (45), Charles Jenkins (?), Charles Todd Jesse (40), Howard Maraman (43), John McKinley McClure (23), George Washington Moore (24), Claud Leon Nutt (7), Daniel Nutt (40), Carl Herbert Perkins (36), Jesse Francis "Frank" Ratliff (34), Annie Mitchell Reed (30), Felix Leonard Riney (23), Augustine Leon "Lee" Roby (28), Harry Mack Samuels (42), Frances "Susie" Sheckles (25), Charles William Shelton (32), John William Showalters (42), Charlie Showalters (35), Susan Simmons (12), James Everett Smith (36), Mike Smith (BC) (37), Mike Smith (Lou) (?), Ethel Thornton (16), Joseph Roscoe Tucker (17), Sarah Elizabeth Ward (37), Henry Wilhite (?), James Marvin Williams (29)

The 1917 wreck has remained an event of interest and fascination down through the years. It has been written about a number of times, and Lloyd "Hog" Mattingly of Lebanon Junction handcrafted a model of the wreck that is remarkably true to the event as told in newspapers of the time. Much of Mr. Mattingly's other work is on display including a model of Paroquet Springs Hotel which is located in the Convention Center in Shepherdsville, and a number of his works are on display in the Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft in Louisville. Several are on display in the Bullitt County History Museum.

The train wreck model was refurbished by Betty Hartley and is now on display on the second floor of the Bullitt County Courthouse, overlooking the actual scene of the wreck.

This webpage and its contents are copyright 2017 by Charles Hartley, Shepherdsville KY. All rights are reserved. No part of the content of this page may be included in any format in any place without the written permission of the copyright holders.

If you, the reader, have an interest in any particular part of our county history, and wish to contribute to this effort, use the form on our Contact Us page to send us your comments about this, or any Bullitt County History page. We welcome your comments and suggestions. If you feel that we have misspoken at any point, please feel free to point this out to us.

The Bullitt County History Museum, a service of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is located in the county courthouse at 300 South Buckman Street (Highway 61) in Shepherdsville, Kentucky. The museum, along with its research room, is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Saturday appointments are available by calling 502-921-0161 during our regular weekday hours. Admission is free. The museum, as part of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization and is classified as a 509(a)2 public charity. Contributions and bequests are deductible under section 2055, 2106, or 2522 of the Internal Revenue Code. Page last modified: 12 Sep 2024 . Page URL: bullittcountyhistory.org/bchistory/trainwreck1917.html