The following article by Charles Hartley was published on 10 Oct 2024 in The Pioneer News.

When you visit the polling place on election day you expect your vote to be private, and your own business, as it should be. But when your elected representatives cast their votes on matters that affect you, be it the local Fiscal Court, the General Assembly in Frankfort, or Congress in our nation's capital, you expect to know how they voted.

This public casting and tabulation of our representative's votes is important. Try to imagine a legislature that meets in private and votes in private, offering us little opportunity to hold them accountable for their actions.

Yet, at the same time, try to imagine showing up on election day and being told to announce your vote in front of all the other voters. Imagine the pressure you might feel to cast a vote that would please others, even if it was not truly how you wished to vote.

Now, cast yourself back to our nation's beginning when a group of men, representing the American colonies, pledged their lives, fortunes, and honor to a declaration of independence from British rule. In that declaration they declared...

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed."

Yet, many of the common soldiers called to fight for these principles would be denied a voice in that government. Those allowed to vote in the earliest elections included, for the most part, only white males who owned property, less than a tenth of the population.

At its creation, Kentucky extended voting rights to all adult white males, eliminating the property requirement. However, because the U.S. Constitution left enfranchisement in the hands of the states, other states were slower to eliminate the property requirement, with North Carolina being the last in 1856.

Another restriction present in our early history was based on religious qualifications. In some places, Jews, Quakers, and Catholics were denied the vote. In others, Baptists were restricted as well. These restrictions were some of the earliest to go.

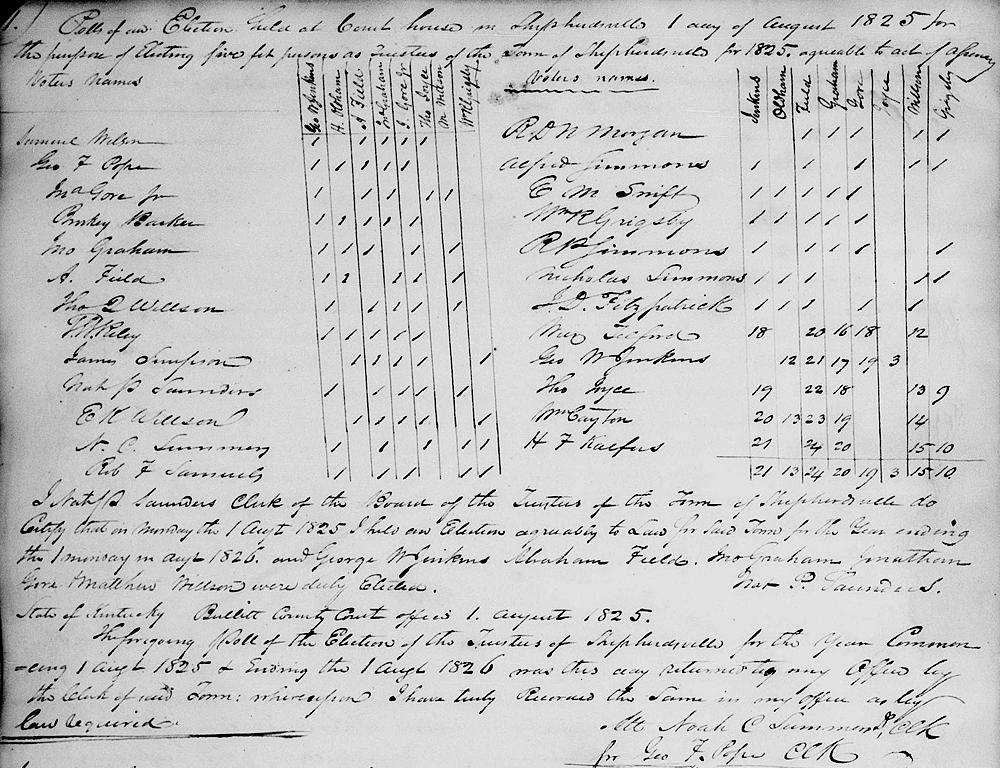

The process of voting has itself undergone significant changes since our nation's birth. For example, look back nearly two hundred years ago to the little town of Shepherdsville. It's the first Monday in August 1825, and time to elect the town's trustees for the next year. Those who can vote are making their way to the courthouse square. They're all men, of course; women have no vote; and those voting are likely just men who own property in the town.

Nathaniel P. Saunders, the town clerk, is responsible for tabulating the votes cast. First, he announces the names of those who have put themselves forward as candidates for office. They include George W. Jenkins, Henry Oldham, Abraham Field, John Graham, Jonathan Gore Jr., Thomas Joyce, Matthew Wilson and William R. Grigsby. Although eight are in the race, only five will be chosen.

Now, if this were today, you would likely expect Saunders to hand out ballots, and have the voters mark them privately and put them in a ballot box.

Instead, with all 25 potential voters gathered around to see and hear, Saunders turns to Samuel Wilson, the first voter, and asked something like, "Who do you vote for, Sam?"

For you see, up until the last decade of the nineteenth century, there were no secret ballots in America. Voters were expected to announce their choices verbally, or later on to turn in pre-printed ballots that were clearly marked to identify for whom you were voting.

So, in this 1825 trustee election, Samuel Wilson gets to go first. When he announces his votes for Jenkins, Field, Graham, Gore and Joyce, there are likely cheers from some and the opposite from others in the crowd.

And so the voting begins. George F. Pope votes next. A man of some local influence, he announces his choices as Jenkins, Oldham, Field, Graham and Gore.

Saunders next turns to Jonathan Gore, one of the candidates, who decides not to vote for himself, casting votes instead for Jenkins, Field, Graham, Joyce and Wilson. As none of the candidates end up voting for themselves, this is likely expected of them.

As the voting continues, some pressure is mounting on the remaining voters, pressure that may include a bit of arm-twisting, and perhaps a bit of liquid refreshments being generously passed around.

Truthfully, in these kinds of elections it was a fairly common practice to sell one's votes to the highest bidder. In a closely contested election, the last handful of voters can profit handsomely should they so choose.

In this election, by the time it gets down to the last three remaining voters, four (Field, Jenkins, Graham and Gore) are assured of victory and two (Joyce and Grigsby) are clearly eliminated. But Henry Oldham and Matthew Wilson each have twelve votes. It is now up to Thomas Joyce to vote. As the least popular candidate himself, he perhaps now has the satisfaction of being able to help determine the remaining victor.

For some reason, Henry Oldham is not participating in the voting, but Matthew Wilson is, and is one of the three who has cast votes for Joyce. Perhaps this is the determining factor leading Joyce to choose Wilson over Oldham, temporarily breaking the tie.

William Cayton is next to vote, and he gives votes to both men, leaving it up to Henry Kalfus, a local tanner and the final voter. He can tie the vote again by voting just for Oldham. Instead he casts another vote for Wilson, giving him the clear victory for the final seat.

We know these results because the clerk appears to have submitted them to the County Clerk who entered the results in Deed Book F on the page between the front index and the first deed entry.

The secret ballot, an official ballot printed at public expense that listed the names of the candidates and was distributed at the polling place and marked in secret, became popular in the late 1880's. In 1888, in Kentucky, a state still voting the oral ballot, the legislature attempted the secret ballot reform in Louisville. After the voting that year, an observer wrote, "The election last Tuesday was the first municipal election I have ever known which was not bought outright." Kentucky would not abandon the oral ballot until 1891.

Following the Civil War, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution granted freedmen full rights of citizenship, and was supposed to prevent any state from denying the right to vote to any male citizen based on race. However, in the decades to follow various restrictions were applied to prevent or discourage African-Americans from voting, particularly in the old South. These included poll taxes, and literacy tests that were unfairly administered. Violence and various forms of retribution including the loss of jobs were also used to control who could vote.

It would not be until the Voting Act of 1965 that restrictions like these were mostly eliminated. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has since seen fit to rule against parts of that law.

Another major advancement occurred with the ratification of the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote in time to participate in the Presidential election of 1920. It had taken more than seven decades to achieve this breakthrough, starting with the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, the first major women's rights convention held in America.

The 26th Amendment, ratified in 1971, required all states to set a voting age no higher than eighteen. Kentucky had already done that in 1955, once again being on the cutting edge of change.

While issues continue to surface regarding who can or cannot vote; issues like requiring photo IDs, denying convicted felons who have served their time, limiting methods of registering, etc., the right to cast your ballot, free from the pressures and restrictions faced by many of our ancestors in days gone by, is a right you should hold dear.

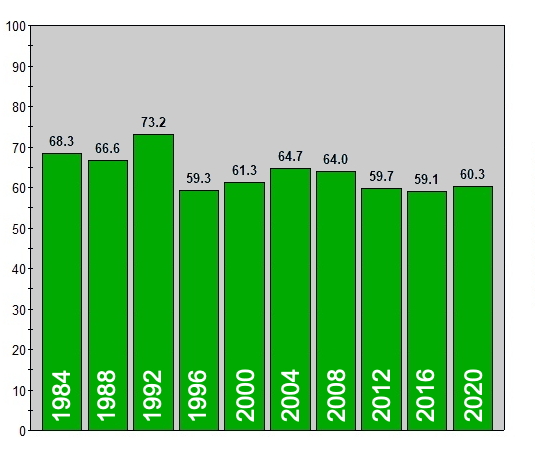

Yet, in the last seven presidential elections, fewer than 65% of registered Kentucky voters have bothered to go to the polls on election day. In 1992, the best of the last 10 elections, one in four registered voters still failed to cast ballots.

| Bullitt County in Presidential Elections | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Registered Voters | Votes Cast | Percent Voting |

| 1984 | 22,017 | 14,573 | 66.1 |

| 1988 | 23,325 | 15,157 | 64.9 |

| 1992 | 25,962 | 19,489 | 75.0 |

| 1996 | 32,489 | 18,910 | 58.2 |

| 2000 | 37,949 | 22,995 | 60.5 |

| 2004 | 44,155 | 28,793 | 65.2 |

| 2008 | 49,357 | 31,716 | 64.2 |

| 2012 | 53,128 | 32,016 | 60.2 |

| 2016 | 57,947 | 36,474 | 62.9 |

| 2020 | 63,342 | 42,180 | 66.6 |

As polarized as politics has become, it's easy to say, "What's the point? My vote won't matter." But your vote does matter; every vote matters! Remember, if you don't vote, you have no right to complain about the outcome.

So, as we approach this year's election on November 5th, please take a moment to remind yourself of how important it is to cast your vote.

Copyright 2024 by Charles Hartley, Shepherdsville KY. All rights are reserved. No part of the content of this page may be included in any format in any place without the written permission of the copyright holder.

The Bullitt County History Museum, a service of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is located in the county courthouse at 300 South Buckman Street (Highway 61) in Shepherdsville, Kentucky. The museum, along with its research room, is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Saturday appointments are available by calling 502-921-0161 during our regular weekday hours. Admission is free. The museum, as part of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization and is classified as a 509(a)2 public charity. Contributions and bequests are deductible under section 2055, 2106, or 2522 of the Internal Revenue Code. Page last modified: 20 Oct 2024 . Page URL: bullittcountyhistory.org/memories/vote.html