The following article by David Strange originally appeared in The Courier-Journal on 5 Dec 2012. It is archived here with additional information for your reading enjoyment.

Do you know about Bullitt County's connection to the "Shakers"? It involves an interesting combination of iron making and adoption.

In Bullitt County from the early 1800's to 1850, and perhaps as late as the 1860's, primitive-but-effective iron furnaces manufactured thousands of tons of iron ingots and castings from the iron ore and limestone dug from the local hills. Three furnaces are known to have existed around the county. Most of one, at Belmont, and part of a second, on south Beech Grove Road, still exist today.

There was also a large "iron works" in Shepherdsville, near the back of what is today the Shepherdsville riverside park. That iron works took the rough ingots from the furnaces and made them into everything from nails, to thick iron plate, to (it is said) even the first "rails" (presumably railroad rails) made in Kentucky.

In fact, some of the wood-stoves at Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill (sometimes called simply "Shakertown") were made at Shepherdsville.

And perhaps through that connection, many children and families from Bullitt County were brought into the unusual religious order over the years of its existence.

By the way, if you are not familiar with Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill, located near Harrodsburg, you really must visit it sometime. It is a massive open village museum, consisting of hundreds of acres of beautiful land and some 38 separate buildings. There is also a nice research facility there.

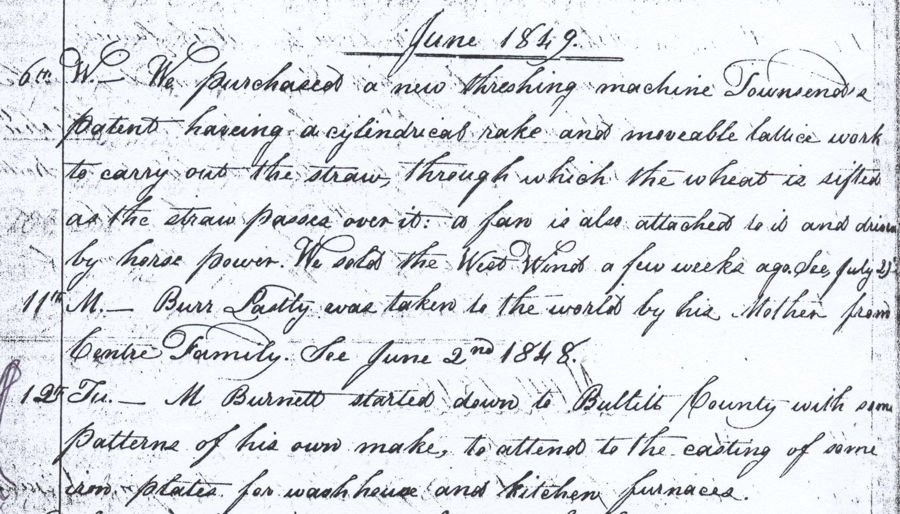

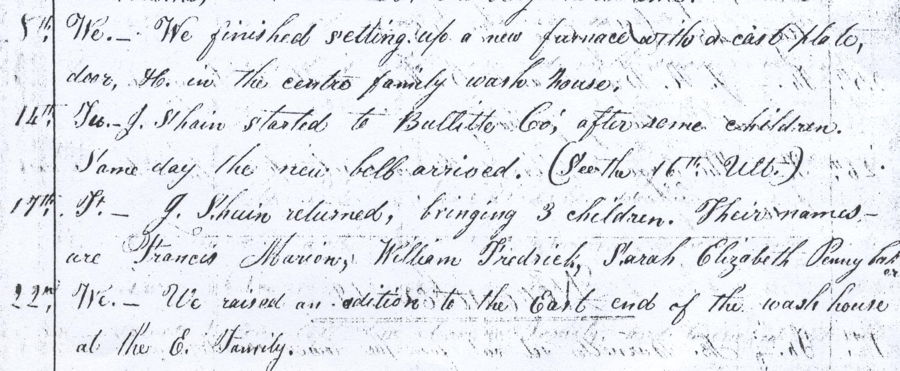

One of the journals archived at Shaker Village, the journal of Zachariah Burnett 1846-1853, mentions Bullitt County, saying in part:

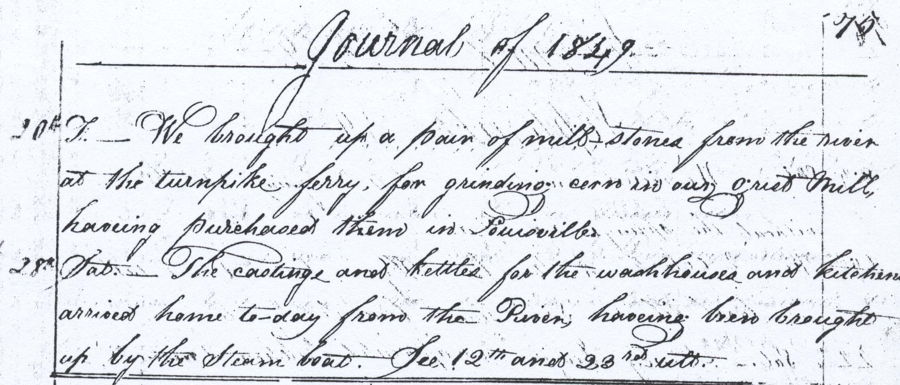

"Tuesday 12th, 1849. ...cloudy with a few drops of rain... M. Burnett started to Bullitt Cty. Furnace with some Furnace Patterns to have some casting done." And later:

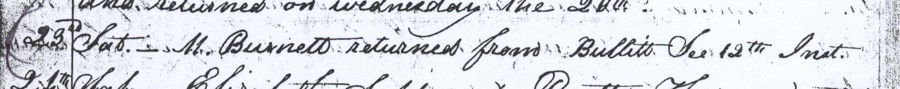

"Saturday 23rd, 1849. ... M. Burnett came home from Bullitt Cty. Iron works with some castings."

The castings were for iron plates for the "washhouse and kitchen furnaces". Those "furnaces," or wood stoves, are still there in the old washhouse today. The Shepherdsville castings, and kettles, for the washhouses and kitchen were delivered by river boat.

The washhouse operation at Shaker Village was used to do the laundry for some 500 men and women. It was quite automated for the time, even using an automatic agitator, powered by a horse outside the building powering a shaft connected to the special inner kettle.

Another of the furnaces was used to dye yarn and cloth.

There are many such furnaces, in several variations including a full iron-box type, throughout the Shaker Village complex. I do not know how many of them were made in Bullitt County, but the ones at the wash house certainly were. And I suspect most of the ones of the same style were made at the Shepherdsville works.

The Shepherdsville Iron Works was apparently begun by John Beckwith about 1813, but suffered many financial difficulties, changing ownership several times.

It went bankrupt in 1850, just a short time after the Shaker Village castings were made. The iron works really never recovered after that, lasting briefly through the Civil War before its fires went out for good.

This leads me to the other half of this story.

Another big connection of Bullitt County and Shaker Village was adoption. The Shakers did not believe in procreation for their followers, strongly following the Biblical verse that men and women should be as brothers and sisters in the Lord.

That presented an obvious problem. How could the sect grow or even survive over time? The answer was, of course, recruiting new members. The Shakers were very active in this at their height, traveling across the state in search of converts. They also took in families in need, or orphans or abandoned children. They hoped the new ones would join them, but never tried to force them to stay, believing a sour or unhappy member to only be a threat to the common tranquility.

And so the Shakers often traveled to Bullitt County, taking in families and adopting children into their congregation.

The sample text mentioned here is just one of many examples of the Shakers coming to Bullitt County. Thus, there are many Bullitt County family names connected to Shaker Village. Some are: Carpenter, Dalton, Deates, Hatfield, Guest, Johnson, Landers, Mariman, Pennebaker, Price, Ricketts, Sapp, Shain, and Spencer. I do not know of any significant genealogical research done in this area of study, so there should be much opportunity for new family history discoveries in the Shaker Village archives.

One of those members of Shaker Village, Tobias Wilhite Carpenter, was brought to Shaker Village at five years old, along with his siblings, after his father died. Tobias left the community around 1840, married Letitia Magruder of Bullitt County, became involved in county politics, and eventually was elected as Bullitt County Judge. He apparently held that office three different times, over the years. He was also state senator from 1874 to 1880; helped establish Eddyville Penitentiary; and was one of Kentucky's first state prison commissioners.

Shaker Village began to decline after the 1860's, and closed out in 1910.

Interestingly, Shaker Village and Bullitt County's early industries shared the same fate. Salt Making in the county, the first industry in Kentucky, began dying out in the 1830's. Iron making in the area lost out to better processes and better iron ore in other areas of the nation, fading away from the county in the 1860's. By 1900, as the Industrial Age was in full swing, Bullitt was settling into a bit of a sleep, its land badly injured from its own early industrial age, not to be awakened again until the interstate road transportation era of the 1950's, a population boom in the 1970's, and finally with the communications, warehousing, and air-transportation days of today.

No one now lives who can remember the days of the iron furnaces in Bullitt County.

Long gone, as well, are the days of the Shakers.

But now you know that there was once a time when the two seemingly unrelated things met.

And many of our families of today were forever affected by it.

Copyright 2012 by David Strange, Shepherdsville KY. All rights are reserved. No part of the content of this page may be included in any format in any place without the written permission of the copyright holder.

The Bullitt County History Museum, a service of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is located in the county courthouse at 300 South Buckman Street (Highway 61) in Shepherdsville, Kentucky. The museum, along with its research room, is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Saturday appointments are available by calling 502-921-0161 during our regular weekday hours. Admission is free. The museum, as part of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization and is classified as a 509(a)2 public charity. Contributions and bequests are deductible under section 2055, 2106, or 2522 of the Internal Revenue Code. Page last modified: 12 Sep 2024 . Page URL: bullittcountyhistory.org/memories/shakerstove.html