The following article by Charles Hartley originally appeared in The Courier-Journal on 11 July 2012. It is archived here with additional information for your reading enjoyment.

Recently 52 members of the families of descendants of Raymond and Alice Nute visited this area from across the country for a reunion. While here they wanted to visit the place where their grandfather maintained an orchard and turkey farm, but all they knew was that the farm was near Medora in Valley Station; and that the family was listed in the 1930 Bullitt County census. They contacted the Bullitt County History Museum in the hope that we might be able to help them find the farm.

After considerable research, a bit of luck, and the helpfulness of one of the area's long-time residents, the farm was located. In the process we also learned a fascinating story.

Ninety-two years ago, Raymond Nute brought his young family from the shoreline of Fall River, Massachusetts to the rugged hills of northwestern Bullitt County to build an orchard. A graduate of the Massachusetts Agricultural College with a degree in Pomology (the study of raising fruit), Nute brought scientific ideas about growing peaches and apples that were met with skepticism at first by his neighbors.

Nute was likely attracted to Kentucky by Henry Bedinger, an Anchorage attorney who had ambitions for some land he had recently obtained. In 1919 Bedinger formed a corporation named the Kentucky Orchard Company and transferred ownership of 85 acres of Bullitt County hillside to the company. He followed this in 1920 with another 44 adjoining acres. Bedinger hoped that Nute could turn the ragged remnants of an earlier orchard into a profitable venture.

Within four years Nute had changed a lot of minds. A 1924 article in the Farmers Home Journal reported on his accomplishments.

"R.E. Nute is one of the most remarkable fruit pioneers in Kentucky, and the constant wonder of his neighbors, who predicted loss from the start because of his ideas on scientific growing.

"About four years ago he was called to Kentucky, put on top of a 'sassafras knob,' where a few old fruit trees nearly dead from neglect and disease reared their heads among the weeds and underbrush and struggled for food among the sassafras roots.

"That hill-top of apparently worthless land is now the wonder of the countryside. To begin with, Mr. Nute had to build a road to the top that auto trucks could navigate. The road was built. A saw mill was constructed so that lumber on the property could be converted into houses and a packing shed.

"The ground was torn up and prepared with the aid of a Fordson tractor and various plows, harrows, cultivators, and the like. Trees by the thousand were planted where only a few old ones were on hand for a nucleus. None in those parts believed in such modern devices as thinning out and spraying and cultivating.

"Nute did. The trees were pruned, dusted, sprayed, cultivated. A big bean spray pump and duster destroyed all insects and pests. Borers were gotten rid of, and lime sulphur dust took care of the upper works of the orchard.

"His packing house is another wonder to fruit growers, who now come for miles to see, and often to buy peaches. Not long ago visitors made the pilgrimage to the top of the hill in such numbers one day that $100 worth of peaches were sold in the front yard."

That "hill-top of apparently worthless land," as the article described it, was located on a ridge of land generally referred to today as "Pendleton Hill." A supplementary article about this land is located on another page.

At the 1925 state fair the Kentucky Orchard Company took the blue ribbon in 14 of 15 categories, prompting the Shepherdsville newspaper to complain that all that fine Bullitt County fruit was erroneously labeled as Jefferson County fruit. The paper went on to say, "Mr. Nute, the manager of the Orchards company is one of the finest peach men in the United States. He knows his business at all times, and this year made a killing for his employers."

That same year, in September, the company bought Luella Pendleton's 103 acres at the top of the hill so that the orchard could be expanded. Then, surprisingly the entire orchard company property was put on the auction block in December and sold to George Hope Lindenberger. The sale notice listed 235 acres of land, 60 acres set in apple and peach trees, a seven room house, three tenant houses and several barns, a variety of farm equipment, and "300 bushels of apples stored with the Merchants Ice and Cold Storage Co."

Lindenberger, president of the Kentucky Tobacco Products Company and a land speculator, was interested in profits, and must have realized that Raymond Nute was the man to provide them. Nothing appears to have changed except the ownership of the orchard company. When Lindenberger died two years later, his family left the running of the farm in Nute's capable hands.

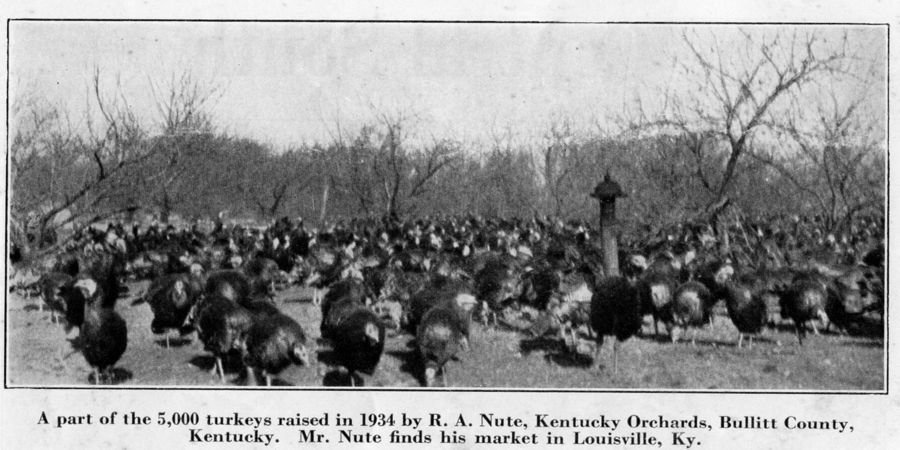

In 1926, Nute acquired a tom and two hens to raise turkeys for his own use, and from that start became interested in turkeys. Always the scientific farmer, he attended a meeting at the College of Agriculture at University of Kentucky to learn more about raising turkeys on a larger scale, and began applying the principles he learned on a gradually increasing scale until by 1930 he had a flock of about 300 turkeys. Then in 1933 the output was 3,000 birds, and in 1934 about 5,000 were raised.

The turkeys not only provided an additional source of income, they were excellent gardeners as well. They provided a natural nitrate fertilizer for the fruit trees, and kept the grounds under the trees free of weeds, insects, and rotting fruit, thus helping to prevent disease.

Nute frequently moved his flocks to different sections of the orchard to clean ground to help prevent diseased turkeys. The few that did become sick were quickly dispatched and burned to keep disease from spreading.

In February 1934, in an interview for The Courier-Journal, Nute explained, "This season I've hatched something like 4,000 eggs in an incubator. Out of that hatch I'll market somewhere between 2,500 and 3,000 fat turkeys. I'm not striving to market all of these birds during the holiday season. I began selling birds in October and I'1l be still marketing them in April. I find there is a steady demand for turkeys over this long period to hotels and fine restaurants."

By this time the orchard had reached over 100 acres, so his ridge top farm had succeeded beyond anyone's expectations. However, this was during the Great Depression, so the level of profit was shrinking. Combine that with the cost of getting their production to market over the narrow twisting dirt road that led off his ridge top, and it is amazing how successful he was.

In 1937 Raymond Nute was selected as the president of the Jefferson County Farm Bureau. He and Alice were active in various farmer's organizations including the fruit grower's association and 4-H clubs for many years.

His flock exceed 7,000 birds in 1937, but profits continued to shrink due to the depression. It is not clear why the Lindenberger family decided to stop farming the land, but the farm was put in the hands of a title company to sell, and the Nutes realized their days there were numbered. By 1938 they were in Vanceburg, in Lewis County along the Ohio River, where Raymond Nute's skills landed him in the county agent's job.

The ridges and hilltops of northwestern Bullitt County are all that remains today of what was once a plateau of upland. The hillsides are the result of stream erosion. Pendleton Hill, shown in this map, is one of the few spots in that area where a significant amount of the former plateau remains.

The very center of the map shows the headwaters of Weavers Run Creek which drains the center of Pendleton Hill.

The Kentucky Orchard Company began in 1920 on the section south of Weavers Run Creek. Weavers Run Road passes through this area today. Later in 1925 the area north of the creek was added to the farm. It includes where Stanley Drive is today.

Travel up Pendleton Hill Road to the top today and you will find a quiet residential area. The orchard is mostly gone; the turkeys have all but disappeared, and the dirt roads have all been paved; but if you use your imagination you can still smell the sweet fruit and hear the turkey gobbles, and remember a scientific farmer who succeeded beyond all expectations. His descendants can be proud of their heritage.

Copyright 2012 by Charles Hartley, Shepherdsville KY. All rights are reserved. No part of the content of this page may be included in any format in any place without the written permission of the copyright holder.

The Bullitt County History Museum, a service of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is located in the county courthouse at 300 South Buckman Street (Highway 61) in Shepherdsville, Kentucky. The museum, along with its research room, is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Saturday appointments are available by calling 502-921-0161 during our regular weekday hours. Admission is free. The museum, as part of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization and is classified as a 509(a)2 public charity. Contributions and bequests are deductible under section 2055, 2106, or 2522 of the Internal Revenue Code. Page last modified: 12 Sep 2024 . Page URL: bullittcountyhistory.org/memories/nute.html |