The following article by Charles Hartley was published on 21 Jun 2015. It is archived here for your reading enjoyment.

I read a recent news article which stated that in Haiti nearly 9,000 people have died from Cholera infection in the last five years. Cholera causes profuse diarrhea and vomiting, which can lead to death by dehydration, sometimes within a matter of hours. Cholera cases are rare in the United States today because of improved water and sanitation. But that has not always been so.

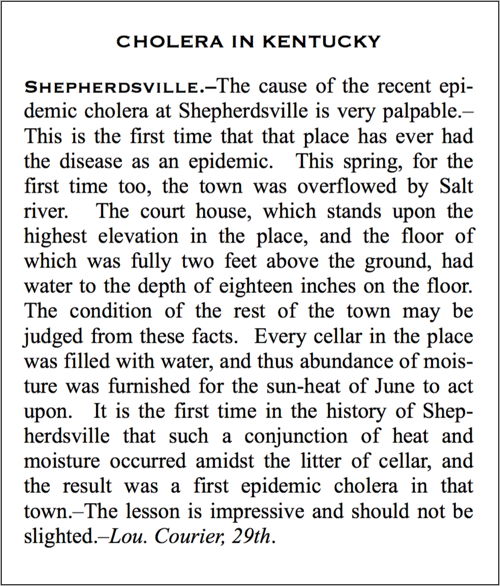

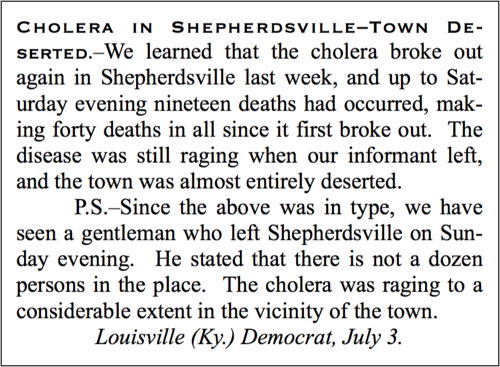

In 1854, Shepherdsville was almost depopulated when cholera swept through the town. On July 2, The Nashville Union and American Sun reprinted an article from The Louisville Courier (shown here) that described how high water had flooded every cellar in town, contaminated the water supply, and provided a breeding ground for the cholera bacteria. By July 8, The New York Times was reporting that as many as forty persons had died in and around that community.

But even earlier, in 1833, the bacteria spread though the lowlands of Louisville and Jefferson County, and was unwittingly carried from there into Bullitt County.

We learned about this episode from a letter written by Dr. Zeno T. Robards, published in The Transylvania Journal of Medicine, and the Associate Sciences in 1834.

Dr. Robards was a son of Joseph and Nancy (Harris) Robards, and grandson of William and Elizabeth (Lewis) Robards. He was a first cousin to Eliza Robards who married Albert Phelps.

He described how Alfred Phelps had come to visit his parents' home east of Shepherdsville. According to Robard's letter, Phelps' neighborhood had experienced many cases of cholera, and Phelps had felt unwell himself. After arriving at the home of his parents, Guy and Sally (Burks) Phelps, he took a turn for the worse.

At that time, one method of treating cholera was by administering calomel (mercurous chloride) which acted as a purgative and killed bacteria. Today we know that it was a toxic remedy that usually did more harm than good, with large doses resulting in death.

According to his letter, Robards administered 1000 grams of calomel to Phelps, but "he nevertheless died about ten hours after I first saw him."

By that time, the water supply had apparently been contaminated, and Sally Phelps, Alfred's mother, became sick as well. But, according to Robards, she "recovered beyond the expectation of any who saw her."

Her sister, Mary Williams was not so fortunate. She began showing signs of the infection on July 9th, and within six hours was dead. Her husband, John Williams suffered for three days, but seemed to improve before taking a deadly turn. According to Robards, "His death was caused by a relapse from leaving his bed too early."

Altogether, Robards identified a dozen people who died from cholera in a matter of days. Besides Alfred Phelps and the Williamses, a four-year-old boy, a Mrs. Simmons, a six-year-old daughter of Richard Simmons, and six slaves all perished.

At that time, the cause of cholera was unknown. The general medical opinion was that it was not a contagious disease. Yet, Robards pointed out in his letter that "in every case, almost without exception, the disease attacked those who waited on the sick. In no case did it attack one who had not been with another who had it."

Medicine in those days was often based on folk remedies and guesswork. For example, Robards advised that one patient be moved "to a house in a corn-field, thinking if malaria was the cause, the house being surrounded with green corn, might have a good effect."

This was perhaps considered because, at that time, a prevailing theory held that the origin of epidemics was due to a miasma, a noxious form of "bad air," that emanated from rotting organic matter.

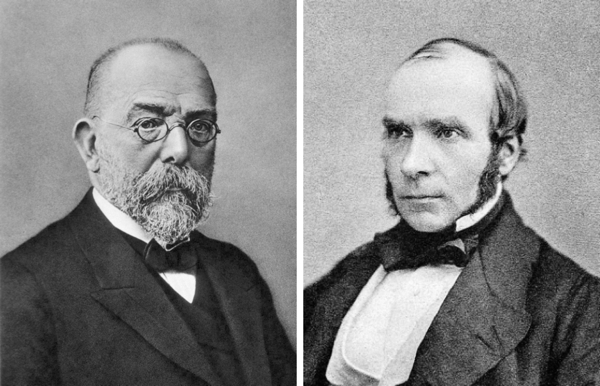

It would not be until 1854 that a London physician named John Snow discovered that cholera is spread by contaminated water. And it would not be until 1883 that the celebrated German physician and pioneering microbiologist Robert Koch identified under a microscope the actual bacillus that caused the disease.

We can be thankful today that clean water supplies and proper sewage treatment protect us from cholera epidemics that still ravage places around the world.

Copyright 2015 by Charles Hartley, Shepherdsville KY. All rights are reserved. No part of the content of this page may be included in any format in any place without the written permission of the copyright holder.

The Bullitt County History Museum, a service of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is located in the county courthouse at 300 South Buckman Street (Highway 61) in Shepherdsville, Kentucky. The museum, along with its research room, is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Saturday appointments are available by calling 502-921-0161 during our regular weekday hours. Admission is free. The museum, as part of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization and is classified as a 509(a)2 public charity. Contributions and bequests are deductible under section 2055, 2106, or 2522 of the Internal Revenue Code. Page last modified: 12 Sep 2024 . Page URL: bullittcountyhistory.org/memories/cholera.html