The following is a modified transcript from the presentation given on the evening of December 20, 2017 at the Ridgway Memorial Library in Shepherdsville in memory of those who were killed or injured in the train wreck that occurred a century ago, December 20, 1917.

Thank you for joining us.

This evening we will think back a century to the terrible event that brought injury and death to so many whose descendants are present with us tonight.

To better understand what life was like then, we need to look even further back to the time when the railroad first came to this area.

Before the railroad arrived, communities like Shepherdsville, Bardstown, and Springfield were mainly connected by poor roads. The railroad would change that, but at a price for some.

The first train to Shepherdsville arrived in October, 1855. It carried city authorities, newspaper men, railroad officials, and as many of the general public as could get aboard. Work was begun immediately on the Salt River bridge.

From the beginning, working on the railroads was dangerous. Accidents were frequent, and deaths were unfortunately common.

For example, in 1882, Engineer George Minott was piloting a heavy freight train north out of Shepherdsville. He had just applied steam to his engine to clear the rise ahead, when a brace of mules suddenly appeared on the tracks.

In the collision that followed, the locomotive left the tracks, followed by several loaded freight cars. Minott was found dead, crushed beneath his locomotive.

On Christmas Eve, six years later, a mail train was standing at Bardstown Junction when an express train rounded the bend at high speed. It crashed into the last passenger car, splitting it apart, before plunging into the next one.

Had that final car been filled with passengers, the death toll would have been terrible. However, it was being towed empty to join another train later. Still, the deaths and injuries that did occur shocked the onlookers.

T. C. Coleman was a Louisville businessman with ties to the railroad. He was responsible for getting a small railroad station located near his home in Bullitt County.

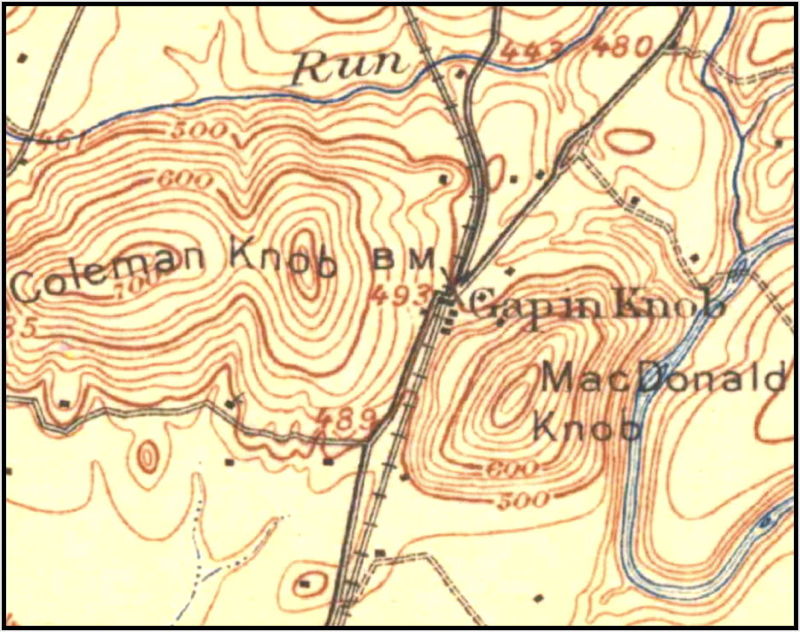

Because of its location between Coleman and MacDonald Knobs, shown here, it bore the name "Gap in Knob."

In the years since then, the railroad bed through the gap has been lowered to beneath the highway. But in those days, trains approaching the station from either direction had to climb a rise to reach the gap.

Additionally, the track north of the station curved around the side of the knob. this reduced visibility, particularly in the early evening at sunset. This was especially true on Christmas Eve, 1899. That foggy evening there was a mist of rain falling, hindering the view.

As the passenger train slowed to a stop at this station, a heavy freight train made its way southward close behind. Because of the fog, the freight engineer did not see the passenger train until it was too late to fully stop.

The freight struck the coach, smashing the rear end. The jolting passed through each of the coaches, creating panic and confusion. The rear panels of the coach were splintered and jagged by the force of the impact. They crushed Cora Carothers against the seat in front, binding her is a vice-like grip. Death came almost instantly.

Also aboard that train were Alice May, Ben Talbott, and Frank Daugherty. None were badly injured, but all would carry this memory 18 years later as they approached another Christmas aboard the Accommodation train.

In this turn of the century photo, you can see the Shepherdsville depot on the right. The Salt River bridge is visible in the far distance. The train shown here was on the northbound tracks. The southbound tracks are on the right, next to the depot. The middle set of tracks were actually a siding to be used when one train needed to allow another one to overtake and pass it.

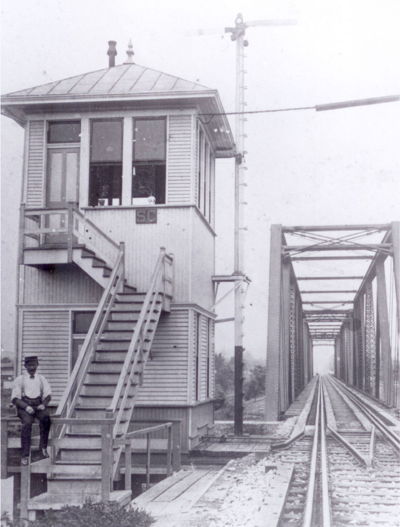

This photo shows the railroad bridge from the south side of Salt River. The railroad had separate north and southbound tracks all the way from Louisville to Lebanon Junction. However, this bridge could only accommodate one train at a time; hence the need for the signal tower, shown here.

Unfortunately, in November 1903, things didn't work as planned. In the early morning hours, two freight trains approached Shepherdsville from opposite directions. A heavy fog rose off the river, obscuring vision, particularly on the south side of the river.

The signal had been given for the southbound train to cross the bridge first, but the northbound train did not see it for the fog, and proceeded toward the bridge.

In the ensuing crash, two were killed, several injured, and both trains were heavily damaged, as noted in the newspaper headlines.

Continuing forward, we now come to 1917, 100 years ago.

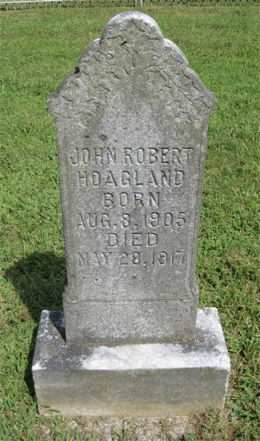

In May, eleven year old John Robert Hoagland was walking along the tracks with Jimmy Morrison when he was struck and killed by a locomotive near his home.

His father, Thomas Hoagland, sued the railroad over his son's death. The case would come to trial just before Christmas, and young Jimmy Morrison was scheduled to be a witness.

Christmas was fast approaching, the first Christmas since America had entered the war; the war to end all wars.

Here in the Ohio River Valley, cold and snowy weather was fast approaching.

Blizzard snow began falling on Saturday, December 8th. By Sunday morning the Louisville newspaper was reporting 16 inches on the ground. High winds drifted it as high as six feet in some places. All traffic came to a near halt. Bitterly cold winds insured that the snow would remain on the ground for days to come.

Temperatures remained below zero on Monday, with little hope of improvement before the end of the week. The railroad was finding it difficult to maintain regular schedules.

But slowly, as the days passed, the snowfall ended, and the temperature crept upward.

The morning of December 20th broke bright and clear. With Christmas fast approaching, families in outlying towns were anxious to take the train to the City. Most wanted to get in their shopping; others had postponed business to attend to.

The morning train pulled away from the Springfield depot, already partly full. It picked up passengers along the way to Louisville, stopping especially at Bardstown and Shepherdsville.

The day passed, and nearly a hundred people met at the Tenth Street depot in Louisville that evening.

While we've not been able to obtain pictures of all the passengers, here are some that we do have. Some pictures come from microfilmed copies of newspapers which accounts for their poor quality.

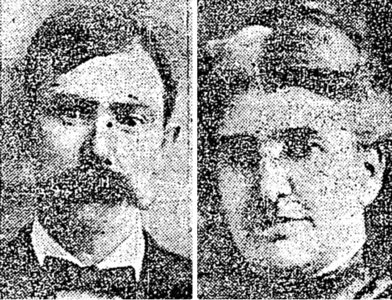

Shown below are Nelson County Attorney Redford Cherry, with his wife Carrie and their son Redford Jr. Also shown here are John and Bettie Phillips. He was Bardstown's town marshal.

Shown here are Mack and Amelia Miller, Frank Daugherty, Mabel Brown Miller, Ben Talbott, and Emily Mashburn, all of Nelson County. Mack was a successful local businessman in Bardstown; Frank was an important lawyer. Mabel was married to T. J. Miller, a bank cashier; Ben Talbott worked in the revenue service; and Emily was married to H. H. Mashburn, a Baptist minister.

Shown below are Nathaniel and Cora Muir, Garnette McKay Moore, Annie Reed, and Susie Sheckles. Nathaniel was a successful Nelson County banker; Garnette was married to Tom Moore, a local distiller; Annie Reed was traveling with Mrs. Louisa Hurst as a nanny for the Hurst baby; and Susie Sheckles was a longtime nurse and nanny for the Simmons family of Bullitt County.

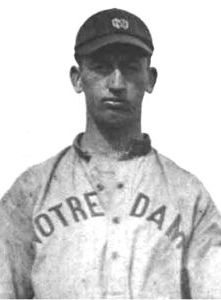

Shown below are Tom Spalding, a student athlete at Notre Dame University; Mary Simms, who was attending St. Mary's School for Girls near South Bend. These two had missed the morning train by minutes, and were anxious to board the evening train for home.

Here too are Frank Nunn, who worked for the railroad, and was on his way to Nazareth College to handle holiday ticket sales; Eliza Craven, who was taking her children, Raymond and Anna, to visit their uncle in Nelson County for the holidays; and Lucas Moore who was a government field agent for the agriculture department.

All these and many more were anxious for the train's departure from Union Station, shown here in this 1906 photo.

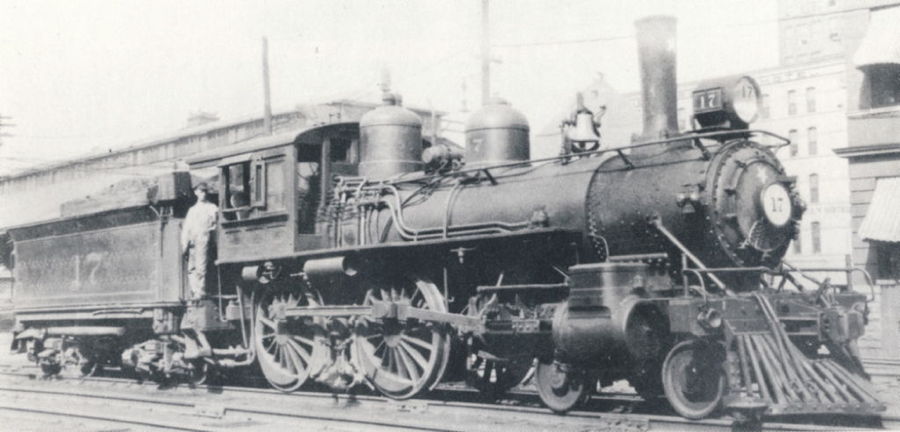

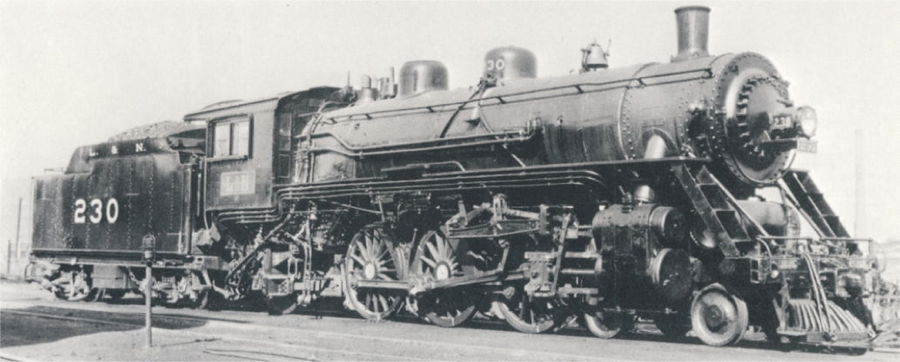

This train was called the Springfield Accommodation. It consisted of the locomotive, a baggage car, and two passenger coaches. The locomotive was a twin to the one shown below in a photo taken in Birmingham in 1923. It was a Class D, American Type, built in 1870 by Baldwin Locomotive Works.

The passenger cars were largely constructed of wood. They were drafty in the winter months, and subject to overcrowding.

At 4:35 the train began its trip south. In 1917, all of Kentucky was on Central Time which would make its departure at 5:35 according to our clock today.

It left on time, but lost precious minutes along the way. By the time it reached Brooks Station, it was already six minutes behind schedule.

Meanwhile, back at the Tenth Street station, an express train had pulled out 18 minutes behind the Accommodation, heading south toward Nashville. It should have left the station ahead of the local train, but it was late. Its engineer needed to make up lost time.

This express train was larger and more powerful. It was pulled by locomotive #230, shown here. This locomotive was a K-4 Class 4-6-2, Pacific Type, constructed, I believe, in L. & N.'s South Louisville shops.

It included nine passenger cars that were mostly made of steel.

The Louisville train dispatcher called the station master at Brooks at 5:08. He suggested that the Accommodation train's conductor head into the siding at Shepherdsville, unless he thought he could reach the Bardstown Junction turn-off before the express train caught up to him.

Without a direct order to take the Shepherdsville siding, Conductor Campbell of the Accommodation decided to make a regular stop at Shepherdsville. He planned to check with that station master to see if he needed to back into the siding.

As Campbell's train was coming to a halt at Shepherdsville, the express train was passing Brooks Station, just five miles north.

Some passengers exited the Accommodation, while others boarded it, including Thomas Hoagland, Jimmy Morrison, and Hoagland's lawyer, Ben Chapeze. Hoagland's case against the railroad had adjourned for the evening, and they were heading home.

Father Eugene Bertello, and David and Howard Maraman were also among those who boarded the train. Father Bertello was on his way to visit a sick parishioner. The Maramans planned to ride the train across the river to their homes.

Campbell questioned the station master who had no information for him. He knew from experience that a number of folks would disembark at the small depot just south of the river, including Mrs. Simmons, her daughter Susan, and Susan's nanny, Miss Sheckles.

He called Louisville for more information, while the station master put up the green color signal to indicate that the track was occupied.

After his call, Campbell ordered the porter to tell the train engineer to pull the train forward and then back into the siding. Meanwhile the express train was just passing Gap-in-Knob. It was practically dark outside.

At this time, the flagman should already have placed flares along the track behind the Accommodation to warn oncoming trains. Perhaps because of the confusion about taking the siding, he failed to do so.

Under train rules, it was the duty of any engineer to approach a station with his train under control and not to pass it unless he received a "proceed" signal. This signal in the night was the changing of a red light to a green. The approaching engineer was supposed to stop unless he actually saw a red light changed to green.

The express train's engineer saw the green signal when he was about 2200 feet from the station. He sounded four short blasts at 1800 feet. This was a signal to the station requesting stop or proceed directions. He saw no change in the light. But past experience led him to think that either the station operator had already changed the light to green, or that it would change before he reached the station. Station operators often did this. At 1200 feet, he signaled again.

When the Accommodation's porter threw the switch to enable his train to back into the siding, the light changed to red.

Seeing this, the express train's engineer applied his emergency brakes. Seconds later he saw the other train in front of him. It was too late.

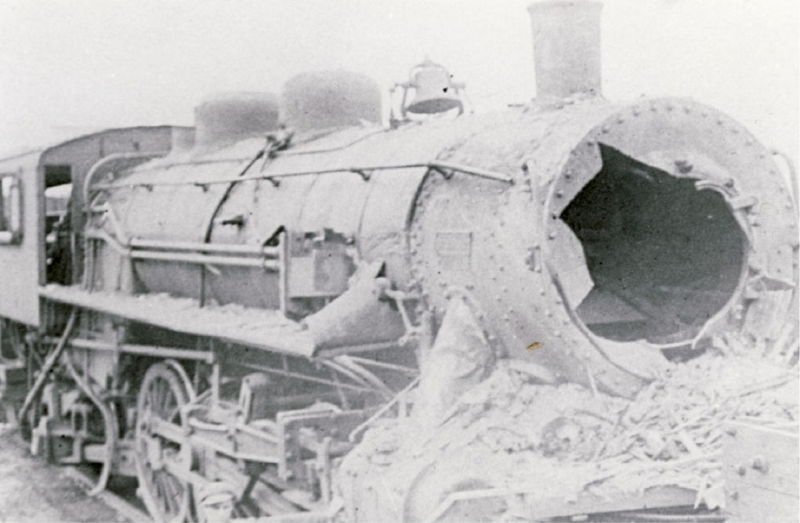

Brakes slowed the express to about 25 miles per hour. But its forward momentum and great weight imploded the back of the rear passenger car, sending fragments of wood and glass forward into the car and its passengers. It continued forward shattering the sides of the car. The roof dropped down on passengers' heads.

The locomotive continued through the length of the car, shattering it completely. It scattered splinters and broken glass debris and bodies to both sides of the track. Other bodies were trapped on the massive engine as it smashed into the next car.

In seconds it was over, but the horror was just beginning.

The scenes you will see next are from pictures taken the next day.

The shattered remains just above the railroad overpass. In the upper right is the Trunnell Hotel where many of the injured were taken. Today the hotel is the home of law offices, and sits just across the street from the Ridgway Library.

What is left of one of the passenger cars.

The same car with debris scattered around it.

The express train locomotive following the crash. Its boiler was smashed, resulting in escaping steam during the crash.

Townspeople and local doctors rushed to the scene, trying to help those who had survived.

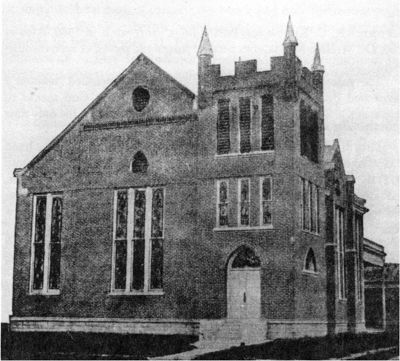

The dead were moved to a make-shift morgue in the Baptist Church building.

A call went out to Louisville, and a special train was sent with doctors and nurses. It transported the wounded to a Louisville hospital. There, more would die from their injuries.

When the tally was complete, forty-nine lives had been lost in this tragedy. Perhaps as many, or more, suffered injuries, many severe. Of these, Mr. Hoagland was one of the worst.

According to a later report in the local paper, "His left leg was broken below the knee, knee cap broken, elbow crushed, face cut all to pieces, head mashed, right side hurt, with several other parts broken."

At the presentation, a

Craven descendent brought

this picture of the baby

Annie Craven to share with us.

His family later remembered that Thomas wore a permanent brace on one leg. He nearly always wore a hat to cover the steel plate inserted in his head.

Moving to the front end of the smoker car had likely saved his life, as well as the lives of Annie Reed, Susie Sheckles, and young Susan Simmons who escaped with minor injuries.

Eliza Craven's body was badly shattered, but she would live.

Her baby girl, Annie, was miraculously tossed from the wreckage, wrapped in her blanket. She landed in a pile of snow, unhurt, and was rescued by townspeople who cared for her until her father arrived from Louisville.

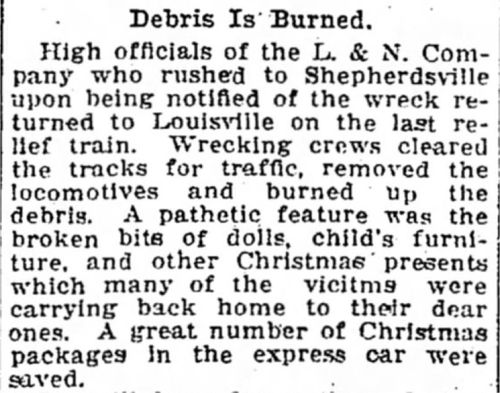

The railroad was quick to clear the tracks. The next day wrecking crews removed the locomotives and burned up the debris. The paper reported that broken bits of dolls, children's furniture, and other Christmas presents were found among the debris.

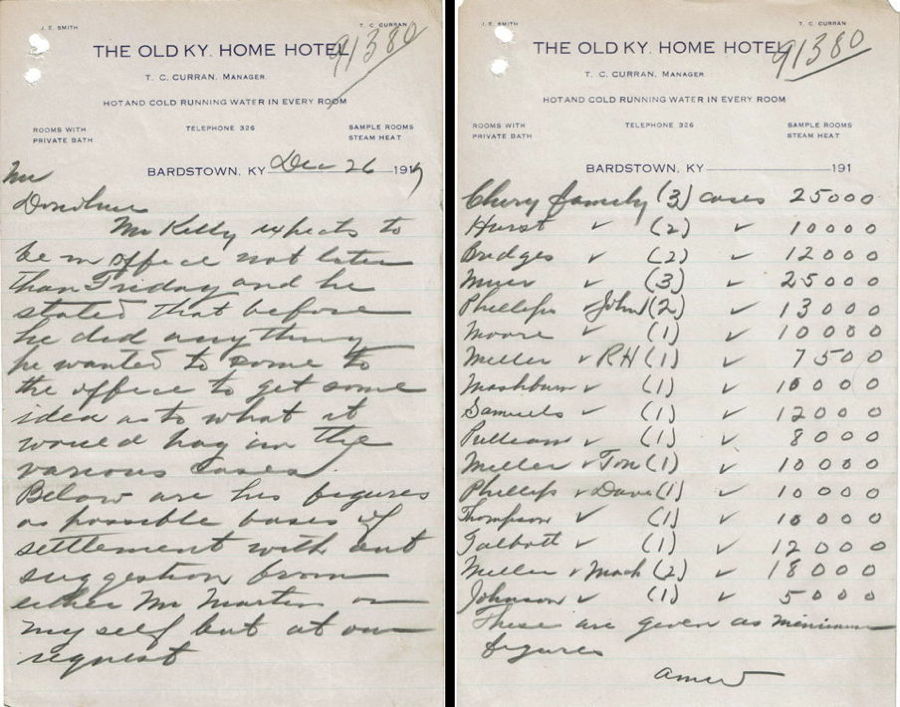

They were also quick to begin trying to determine what financial costs this tragedy would bring for the company. The day after Christmas, A. M. Warren, chief law agent for the railroad was in Bardstown where he would make a list of the minimum amounts various families might accept as compensation for their loses. Many of these cases would find their way into the court system before being settled.

Everyone wanted to know who to blame for this terrible accident. The railroad fixed the blame on the Accommodation's conductor, Mahlon Campbell, and its flagman, Lawrence Greenwell, and on William Wolfenberger, the engineer of the express train.

The Interstate Commerce Commission agreed, but added an indictment of the railroad itself for failing to maintain a manual block system rather than the time-interval system then in place. The time-interval system was supposed to prevent trains from being closer than ten minutes traveling time, but failed to do so this time. A manual block system permitted only one train at a time along a set block of track.

As we brought this presentation to a close, we asked that those present stand in honor and memory of those who lost their lives in this tragedy, as Barbara Bailey read their names. Their names are presented below.

In Memoriam

Father Eugenio Bertello

Joshua Bethel Bowles

Hollie Bridges

Josie Bridges

Mahlon Campbell

Carrie Barkhurst Cherry

Redford Columbus Cherry

William Redford Cherry, also known as Redford Jr.

Raymond Thomas Craven

George C. Duke

Virginia Frances Duke

Lawrence Greenwell

Henry Zollicofer Hardaway

Martha Jones "Mattie" Harmon

Joseph Raoul Hurst

Louisa Losson Hurst

Catherine Cundiff "Kate" Ice

Charles William Johnson

Silas C. Lawrence

David Henry Maraman

Emily Haycraft Mashburn

Elizabeth McElroy

Amelia Smith Miller

Walter McMakin "Mack" Miller

Lillian Jones Miller

Mabel Brown Miller

Garnette McKay Moore

Lucas Moore

James Hartwell "Jimmy" Morrison

Cora May Shadburne Muir

George Shadburne Muir

Nathaniel Wickliffe Muir

Frank Linnis Nunn

Estella Harris Nutt

Forrest Overall

Maggie Overall

David Phillips

Elizabeth Wright "Bettie" Phillips

John T. Phillips

Mary Alice May Pulliam

Emory Beamis Samuels

Thomas William Schaefer

Carrie May Brown Simmons

Mary Alethaire Simms

William Thomas Simms Spalding

James W. Stansbury

Ben Talbott

James W. Thompson

N. H. Thompson

There is much more to this story. If you are interested in learning more, Charles Hartley has written a book about it that is available from the Bullitt County History Museum. All proceeds from its sale go to support the museum's work.

The book is also through Amazon.com by following this link.

If you, the reader, have an interest in any particular part of our county history, and wish to contribute to this effort, use the form on our Contact Us page to send us your comments about this, or any Bullitt County History page. We welcome your comments and suggestions. If you feel that we have misspoken at any point, please feel free to point this out to us.

The Bullitt County History Museum, a service of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is located in the county courthouse at 300 South Buckman Street (Highway 61) in Shepherdsville, Kentucky. The museum, along with its research room, is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Saturday appointments are available by calling 502-921-0161 during our regular weekday hours. Admission is free. The museum, as part of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization and is classified as a 509(a)2 public charity. Contributions and bequests are deductible under section 2055, 2106, or 2522 of the Internal Revenue Code. Page last modified: 12 Sep 2024 . Page URL: bullittcountyhistory.org/bchistory/tw_100yr_transcript.html