A Report on a Research Trip to Pleasant Hill at Shaker Village, Kentucky June 26, 2009.

"Iron Stoves and Adoptive Children"

by David Strange

During Bullitt County's early pioneer history it was a prominent source for iron. From the early 1800's to 1850, and perhaps as late as the 1860's, primitive-but-effective massive iron furnaces manufactured thousands of tons of iron ingots and castings from the iron ore and limestone dug from the local hills. Three furnaces are known to have existed around the county. Most of one, at Belmont, and part of a second, on south Beech Grove Road, still exist today.

There was also a large "iron works" in Shepherdsville, near the back of what is today the Shepherdsville city park, where ball fields are being constructed at the time of this writing. That iron works took the rough ingots from the furnaces and made them into everything from nails, to thick iron plate, to (it is said) even the first "rails" (presumably, railroad rails) made in Kentucky.

Several years ago, I was told that the wood-stoves at Pleasant Hill at Shaker Village (sometimes called simply "Shakertown") were made at Shepherdsville. Indeed, if asked, the tour guides at Shaker Village would tell you so. I also learned that many children and families from Bullitt County were brought into the unusual religious order over the years of its existence.

By the way, if you are not familiar with Pleasant Hill at Shaker Village, you really must visit it sometime. It is a massive open village museum, consisting of hundreds of acres of beautiful land and some 38 separate buildings. For more information, check their web site, www.shakervillageky.org, or call 800-734-5611.

On June 29, 2009, I went to Shaker Village to try to document the stories of the wood stoves, and to learn more about the family connections.

That morning, by appointment, I met Ms. Larrie Curry, an archives specialist there, who was very kind and generous to such an amateur researcher as myself. I was immediately impressed with how they had blended the administration building and the archives building into the village. From the outside, I would have been certain they were just barns. But inside they were modern and nice. The archives building in particular, which included the main research library, was indeed actually inside a barn. The modern concrete building had really been built to fill the inside of a large barn on the property.

Impressive.

But on to the research.

An advantage to researching the Shakers is that they considered writing daily journals an important thing to do. So there is a large body of writings. The disadvantage is that most all of it is still only in its original hand-written form. So it is very time consuming to search.

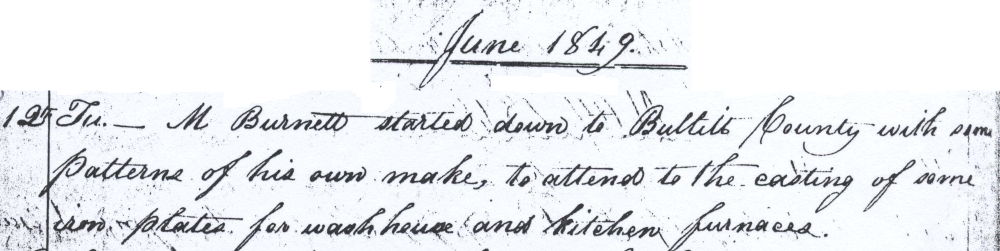

But we were in luck. One of the journals, the journal of Zachariah Burnett 1846-1853, has been transcribed to digital, computer-searchable format. On coming upon that, Larrie and I did several text searches on it for references to "Shepherdsville", "Bullitt County", "Iron Works", etc. We hit pay dirt with just "Bullitt". It said in part:

"Tuesday 12th, 1849. .....cloudy with a few drops of rain..... M. Burnett started to Bullitt Cty. Furnace with some Furnace Patterns to have some casting done."

And later:

"Saturday 23rd, 1849. .... M. Burnett came home from Bullitt Cty. Iron works with some castings."

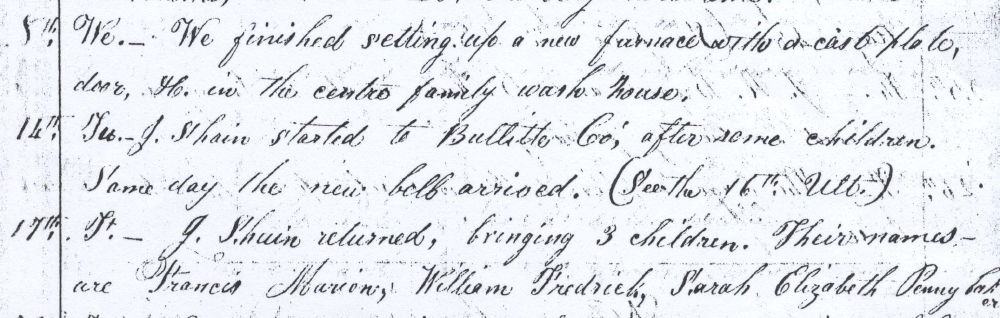

This alone did not tell us much. But it gave us a date for further research in other journals. And indeed, we then found the following text in another journal, shown from a photo copy:

This gave us a bit more detail. The castings were for iron plates for the "washhouse and kitchen furnaces".

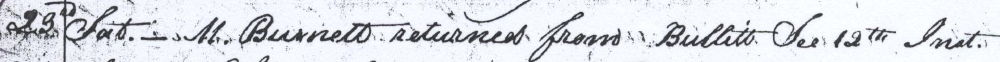

We also found:

And:

That gave us more usable detail. The Shepherdsville castings, and kettles, for the washhouses and kitchen arrived by river boat. By the way, my wife and I stayed a night at Shaker Village as well, during which we went down to that same steam boat site on the Kentucky River and enjoyed a nice evening on a paddle-wheel boat ride.

So, we know that M. Burnett had traveled to Bullitt County with his "patterns" (sometimes drawings, but usually wooden molds for the sand castings) for the wash house and kitchen "furnaces", as well as kettles, returning on the 23rd. Delivery was made June 28, 1849 by riverboat. I suspect the castings were shipped via boat down the Salt River, by way of Pitts Point, up the Ohio River to what is now Carrolton, and thence up the Kentucky River to its destination.

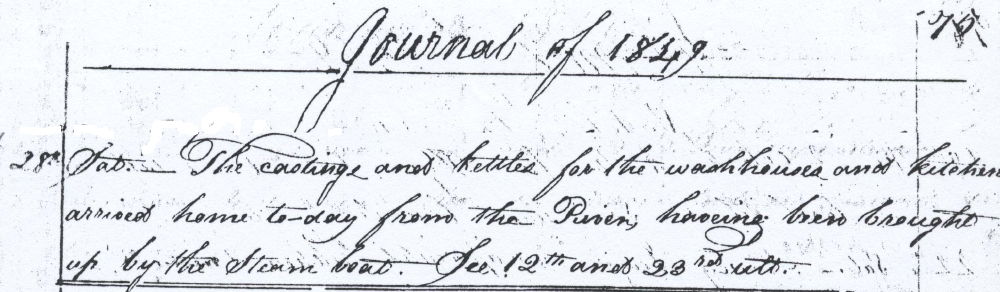

In checking with the folks at Shaker Village, we further found, to our great good luck, that a new wash house had been built that same year, and that it, and its original wash furnaces, were still in place.

The photo at right is of that same, original wash house furnace that was made in Shepherdsville in 1849. It was meant to help do the laundry for some 500 men and women. Note the thick cast iron plate on top; the kettles, and the cast fire-door. This wash furnace even had an automatic agitator, powered by a horse outside the building powering a shaft connected to the special inner kettle.

Next is a photo of another of the furnaces in the same wash house. This one was used to dye yarn and cloth.

There are many such furnaces, in several variations including a full iron-box type (shown further down the page), throughout the Shaker Village complex. We have not yet confirmed how many of them were made in Bullitt County, but we certainly know the ones at the wash house were. And we suspect most of the ones of this style were made there.

What I have not yet been able to confirm is whether the more elegant heating stoves, shown in the photo below next to one of the iron-box types, were also made in Bullitt. Verbal history says that they too were made there, but the style is so different I have to wonder.

But that is research for another day. There is a tantalizing mention in the records, for example, that in March 1, 1845, Barnett and Robert Johns went to Louisville to get castings for a grist mill. Did the writer really mean Shepherdsville?

The Shepherdsville Iron Works was apparently begun by John Beckwith about 1811 or so, but suffered many financial difficulties. It was taken over by Query(Quary) and Tyler about 1840.

Interestingly, it went bankrupt again in 1850, just a short time after the Shaker Village castings were made. It really never recovered after that, perhaps lasting briefly through the Civil War before its fires went out for good. More information on that can be found here.

On Another Note: Bullitt County people and their Shaker Village connections. Just a few more lines down the 1849 Shaker Village journal, we found the following:

The Shakers did not believe in procreation for their followers, strongly following the Biblical verse that men and women should be as brothers and sisters in the Lord. That presented an obvious problem. How could the sect grow or even survive over time? The answer was, of course, recruiting new members. The Shakers were very active in this at their height, traveling across the state in search of converts. They also took in families in need, or orphans or abandoned children. They hoped the new ones would join them, but never tried to force them to stay, believing a sour or unhappy member to only be a threat to the common tranquility.

The sample text above is just one of many examples of the Shakers coming to Bullitt County. Thus, there are many Bullitt County family names connected to Shaker Village. Some are: Carpenter, Dalton, Deates, Hatfield, Guest, Johnson, Landers, Mariman, Pennebaker, Price, Ricketts, Sapp, Shain, and Spencer. I do not know of any significant genealogical research done in this area of study, so there should be much opportunity for new family history discoveries in the Shaker Village archives.

One such new member, Tobias Wilhite Carpenter, was taken to Shaker Village at five years old, along with his siblings, after his father died. Some other family members were already believers there. But Tobias left the community as a young man around 1840, married Letitia Magruder of Bullitt County, and eventually became the Bullitt County Judge. He apparently held that office three different times, over the years, and might be an interesting figure for someone to do a biography on sometime. He was state senator 1874-80, helped establish Eddyville Penitentiary, and was one of Kentucky's first state prison commissioners. There is some significant history on him, but no definitive work that I know of.

And there is much more work for someone to do on so many of the names and subjects only briefly touched on in this report. I do not know if I will ever be able to get back to this interesting connection between Bullitt County and the intriguing Shaker Village at Pleasant Hill.

I certainly encourage someone to do so.

The Shakers eventually died out in Kentucky in the early 1900's, though a few remain in America's northeast. Their decline is attributed more to a change in times than anything else. After the Civil War, there was much less interest in the quiet, introspective, monastic rural life espoused by the Shakers. The Industrial Age was beginning in earnest and restlessness for "change" and "progress" enveloped the thoughts of the nation.

Interestingly, at that same time of industrial expansion, Bullitt County's main industries were in decline. Salt Making in the county, the first industry in Kentucky, began dying out in the 1830's. Iron making in the area lost out to better processes and better iron ore in other areas of the nation, fading away from the county in the 1860's. By 1900, as the Industrial Age was in full swing, Bullitt was settling into a bit of a sleep, its land badly injured from its own early industrial age, not to be awakened again until the railroad days of the 1940's, again in the interstate road transportation era of the 1960's, and finally with the communications, fast-turnaround warehousing and air-transportation days of today.

David Strange

Bullitt County History Museum

If you, the reader, have an interest in any particular part of our county history, and wish to contribute to this effort, use the form on our Contact Us page to send us your comments about this, or any Bullitt County History page. We welcome your comments and suggestions. If you feel that we have misspoken at any point, please feel free to point this out to us.

The Bullitt County History Museum, a service of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is located in the county courthouse at 300 South Buckman Street (Highway 61) in Shepherdsville, Kentucky. The museum, along with its research room, is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Saturday appointments are available by calling 502-921-0161 during our regular weekday hours. Admission is free. The museum, as part of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization and is classified as a 509(a)2 public charity. Contributions and bequests are deductible under section 2055, 2106, or 2522 of the Internal Revenue Code. Page last modified: 14 Sep 2024 . Page URL: bullittcountyhistory.org/bchistory/shaker/shakertrip.html

[an error occurred while processing this directive]