The following article by David Strange was originally published on 1 May 2016.

While telling you a story in this space last Sunday, I mentioned "The Poor Farm," and several of you have asked what that was. I told the full story back in 2013, but let me tell you a brief version now.

Most of us now living have become so accustomed to social security programs, that it is hard to imagine that not so long ago there was virtually no help for people in need. No old age pensions; no social security.

Often nothing at all except for the mercies of those who chose to help.

"Poor Farms" were county or town-run residences where paupers (mainly elderly and disabled people) were supported at public expense. They were common in the United States beginning in the middle of the 1800s, and declined in use after the Social Security Act took effect in 1935.

Most counties had them in some form. I am told that Jefferson County, Kentucky, had one as did Hardin county. Bullitt County Fiscal Court started its county poor farm on April 10, 1903.

The Court voted unanimously "to build 2 box houses for White & Colored Poor Houses." They also built a corn-crib, meat house, and a coal house, and decided to hire "a married man" to manage the farm. A manager got to use the land to farm, and in return helped take care of the "inmates."

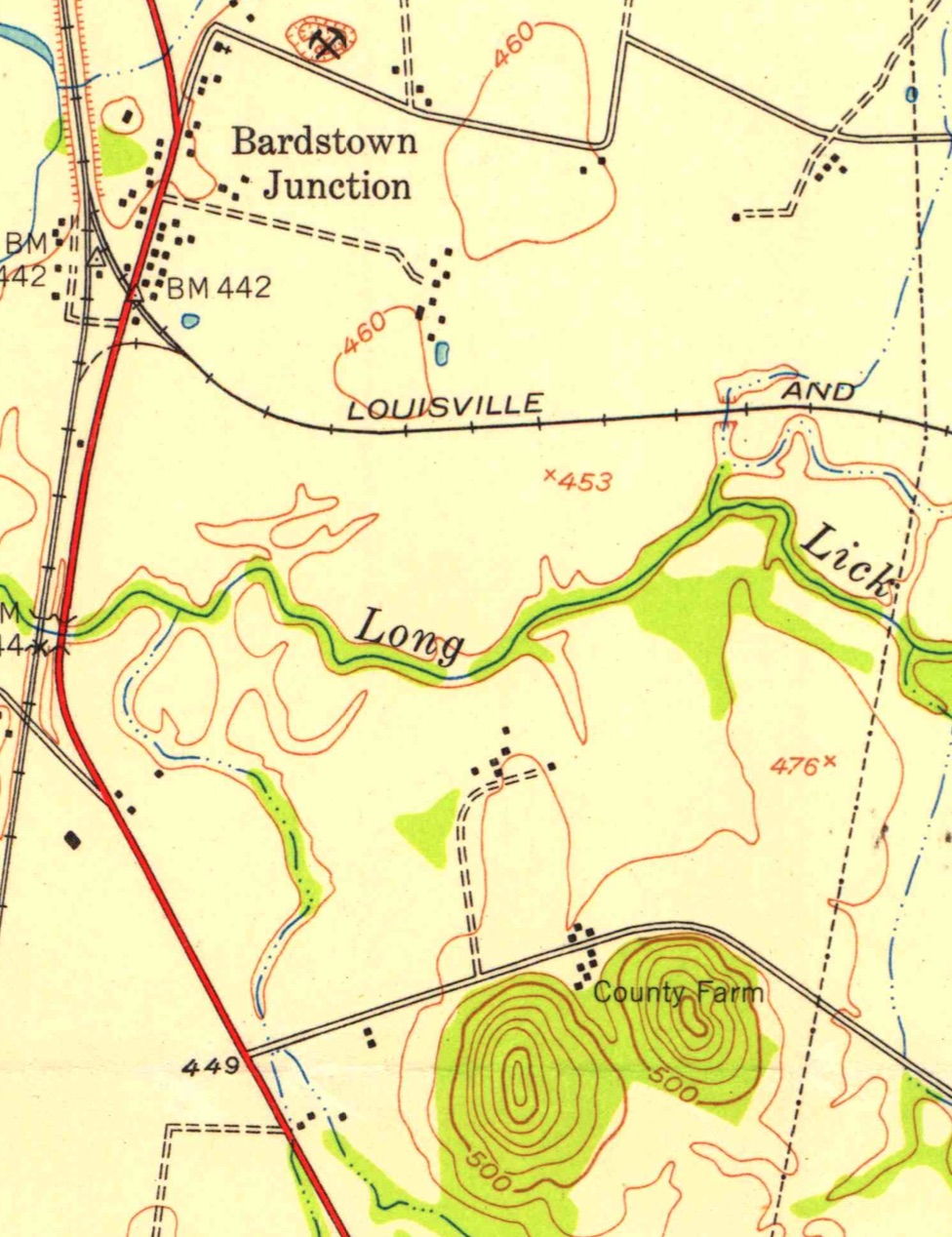

Today, the intersection of Interstate 65 and Highway 245 cuts the land into three pieces where the old Poor Farm used to be. But of course, all of that land was in one piece before Interstate 65 came along.

Joe Raley, who still lives nearby, remembers it very well.

He was the caretaker of the farm for many years, as was his father before him, for over thirty-five years. Joe's father, John Raley, became caretaker of the Poor Farm in 1942, moving his family into the caretaker's home on the farm.

The Raleys paid rent to the county for use of the land to raise crops and livestock, and to live in a house on the farm, built for that purpose. When the county judge would send someone to the poor farm, the Judge would take off a portion of the rent owed by the Raleys. The Raleys were, in return, obligated to feed, bathe, and generally take care of the people. A doctor would come by sometimes, when needed.

A Fiscal Court order stated in January 8, 1942, "The renter to take care of the paupers, feed them, furnish fuel for them. County to furnish clothing and bed clothing and they live in the county property, renter to do all washing and keep paupers clean."

Residents at the farm were mostly old folks. There were sometimes families with children, but not often.

Charles Shelton told me about his memories of the farm. "Most couldn't do much," he said. and "had long-since told all the stories they knew, so they mostly just sat there."

Joe Raley remembers one elderly woman who couldn't get around, except by scooting around the room in her chair. Though doing their best for the times, these were hardly the modern care homes of today.

When the woman died, she was buried at the small cemetery that had developed there. The county would also bury "John Does" in the graveyard, such as unidentified transients killed on the train tracks, or people who just had no family and nowhere else to be buried.

As many as twenty-two people at a time lived on the Poor Farm, but that was before Joe Raley's time. With the creation of old age pensions by the government, the number of Poor Farm residents decreased as "Homes" started coming into existence that were willing to take the pension money for their care. In 1954, some of the farm was sold for a right-of-way for the new "Kentucky Turnpike" toll road, later to become Interstate 65.

In 1959, the state bought more land to add access ramps to the expressway. In 1981, it was widened still more, requiring the old graveyard to be moved. Only one of the original gravestones was moved. The state paid for forty-five small granite markers to be placed at the new gravesite, like the one shown here.

Much of the hillside, where the graveyard had been, was removed to make way for the southbound access ramp.

Joe Raley continued renting some of the land to farm on until 1977, but it was becoming less and less worthwhile. In 1980, the re-forming County Fairboard leased a large portion of the farm for a county fairground.

In April, 1981, the Pine Creek Forest Fire District, later to become the Southeast Fire Department, obtained a ninety-nine-year lease for some land where the houses once were, to build a firehouse. A new county animal shelter was developed behind that.

Talk began about building a new college campus on the remaining northwest corner, but that effort seems to have faltered in recent years.

And memory began to fade about the old Poor Farm, and why that land is owned by the county in the first place.

Joe Raley knows.

Now you do too.

Copyright 2016 by David Strange, Shepherdsville KY. All rights are reserved. No part of the content of this page may be included in any format in any place without the written permission of the copyright holder.

The Bullitt County History Museum, a service of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is located in the county courthouse at 300 South Buckman Street (Highway 61) in Shepherdsville, Kentucky. The museum, along with its research room, is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Saturday appointments are available by calling 502-921-0161 during our regular weekday hours. Admission is free. The museum, as part of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization and is classified as a 509(a)2 public charity. Contributions and bequests are deductible under section 2055, 2106, or 2522 of the Internal Revenue Code. Page last modified: 12 Sep 2024 . Page URL: bullittcountyhistory.org/memories/poorfarm2.html